THEORY OF THE END - Volume III: The Fortunate Eon

The third volume of "THEORY OF THE END, Version 2"

A Note

This is the final volume of the improved and expanded edition of Theory of the End, with this entry compiling essays previously named “parts 16 to 21” and ending with the “conclusion” essay. Chapter 11, “The Mechanical Phantom,” is entirely new material, but I believe that it fits well with the other essays here.

If you are new to this series, I suggest starting with either the Introduction or “Volume I: The Future is Canceled.”

With that out of the way, please enjoy.

Chapter 11: The Mechanical Phantom

“We are ghosts of the concrete world,

Genetic codes of a dying breed.

Will I be left behind?

Sounds of a playground fading.”

-In Flames, from “Sounds of a Playground Fading”

“It is a strange fact, and one which appears never to have received proper attention, that the strictly ‘historical’ period… goes back exactly to the sixth century before the Christian era,” writes the French Metaphysician Rene Guenon in his 1927 work “The Crisis of the Modern World.” It is, he states, “as though there were at that point a barrier in time impossible to penetrate by the methods of investigation at the disposal of ordinary research.” He continues:

Indeed, from this time onward there is everywhere a fairly precise and well-established chronology, whereas for everything that occurred prior to it only very vague approximations are usually obtained, and the dates suggested for the same events often vary by several centuries.

This apparent wall has resulted in a shroud of mystery around early human civilization, one which has been seized upon by writers like Graham Hancock, who has spent his career searching for evidence that there existed in that distant time societies far more advanced than we have previously considered. “It must be considered as a reasonable hypothesis,” he writes in his popular 2015 book “Magicians of the Gods,” “that worldwide myths of a golden age brought to an end by flood and fire are true, and that an entire episode of the human story was rubbed out in those 1,200 cataclysmic years between 12,800 and 11,600 years ago — an episode not of unsophisticated hunter-gatherers but of advanced civilization.”

To Hancock, his endeavor is one of human self-discovery, the idea that we could truly know ourselves by looking towards the echoes of the past. “It’s extraordinary to be alive at all. Just to, you know, to be in a human body,” he says in a 2025 YouTube interview on the channel “Before Skool,” continuing: “All of this is a miracle and a mystery that’s wrapped up in the larger mystery of what we are as a species and the origins of human civilization.”

Other thinkers, like the early 20th century Japanese educator Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, have thought of early man as “an extremely powerless and pitiable being” who came into greater control of himself and his environment through the application of technique, culminating in technological modernity. In one of his texts, he quoted the book “Applied Sociology” by the American Sociologist Lester F. Ward, saying: “All applied science is necessarily anthropocentric, Sociology is especially so.” Men like Ward and Makiguchi believed that it was through such scientifically-minded means that man would finally come to a greater understanding of himself, with Ward writing: “Pure sociology is simply a scientific inquiry into the actual condition of society. It alone can yield true social self-consciousness.”

The irony of this proposal is that, despite the vast expansion of “science” and its countless technical applications in our daily lives, humans seem less sure about themselves and their place in the universe than ever before. Our desacralized nature leads not to greater understanding and unity, but towards profound splintering and ultimately atomization. Makiguchi himself realized that something integral was missing from the increasingly irreligious and materialistic outlook of his time, writing back in 1935: “When we speak of religious faith, this may appear as the monopoly of religionists, and thus something that youthful educators wish to distance themselves from, but if we speak of belief, trust, confidence, or conviction, we understand that these form the necessary foundations for daily life.”

Makiguchi, who professed a longstanding “sense of unease, of groping [his] way in the dark,” eventually converted to Buddhism in 1928, when he was nearly sixty years of age. “My lifelong tendency to withdraw into thought disappeared,” he wrote in 1935 regarding his conversion. “My sense of purpose in life steadily expanded in scope and ambition, and I was freed from all fears…” In a 1937 autobiographical piece, he recounted how his religious awakening had led to a realization of his prior work’s deficiency:

In the midst of [writing the book “The System of Value-Creating Pedagogy” (Jpn: Sōka kyōikugaku taikei, 創価教育学大系)] or, rather, as I was just approaching completion after the release of the first volume, through the faith and understanding of the Lotus Sutra I was able to develop, I was astonished to see that the unconscious progress of my thinking corresponded with the teachings of the Sutra. As I continued to advance in this, I came to realize, with an even greater surprise and joy, that the essential core of the Lotus Sutra represents the totality and basis of the Dharma/laws/principles/methods of daily life and that, relative to this, the rational educational methods called for in my value-creating pedagogy are only partial and peripheral. As I examined the matter more closely, I noticed that there was a crucial lapse in the criteria for the judgment of value I had been proposing. Now, for the first time, my ascertainment of good and evil became fully accurate.

It seems that even a man of scientific sensibilities who had believed in the narrative of human progress like Makiguchi could see that the technical drive for rationality and quantitative material focus which characterized the sociology of his time had left it minus something, and it was the ancient wisdom of supreme unity outlined in the Lotus Sutra that filled the gaps with something transcendent. His quest to outline the human conception of “value,” it turned out, could only evolve to its highest form once he went beyond the constraints of modern scientific rationality. In Andrew Gebert’s essay “The Roots of Ambivalence: Makiguchi Tsunesaburo’s Heterodox Discourse and Praxis of ‘Religion,’” he describes the evolution of Makiguchi’s “value-creation” theory as follows:

Makiguchi posited three forms of value: Beauty, Gain, and Good, with the last defined as that which enhances and extends the shared life of humans in community. In his original formulation of this system, Makiguchi assumed that judgments regarding the value of Good could only be made by and within individual societies. This appears to be the “crucial lapse in the criteria for the judgment of value” that came to Makiguchi’s attention through his study of the Lotus Sutra. While Makiguchi does not explicitly indicate the content of this discovery, he clearly celebrates it: “Now, for the first time, my ascertainment of good and evil became fully accurate” (Makiguchi 1981–1988, [1935] 8:411). From the text… it can be seen that the standard of good and evil that became clear to him was one that transcended the contemporaneously prevailing values of his society and, in this sense, aspired to the universal.

“Religion,” if we are to use such a word to describe frameworks like Buddhism (for it can be tricky to define, especially considering man’s current tendency to view it merely as a grouping of societal functions and dynamics), is our primary connection to the remote past, a means to potentially understand what we’ve lost along the way. People pass away and landmarks crumble, worn and weathered by the slow crushing strength of the natural world, yet we can still pick up ancient scriptural texts at the local bookstore and enter into the minds of those who lived long, long ago.

Exactly how much we have lost in our never ending pursuit of “progress,” however, is a matter of much debate. While Makiguchi saw old scriptural texts drenched in mysticism like the Lotus Sutra as holding great importance to understanding the human condition and our place in the cosmos, many of his contemporaries would have disagreed. “Religion is a product of reason,” Lester F. Ward wrote, placing religion as a consequence of primitive fear of the unknown and inconceivable.

To Ward, early man was “in constant terror of dire visitations from malignant spirits,” and had created religion as a technique to ward off invisible dangers; much more a societal function than a supreme truth. “But it soon overstepped the narrow limits of this primordial duty, and began to guide men to the satisfaction of desires which were disconnected with function and even destructive of it.” Both Ward and others influenced by the Positivist philosophy of Auguste Comte thought religion was characteristic of a stage humanity had to pass through and eventually overthrow in favor of new intellectual heights. Similar views still permeate society today, in particular the idea that men of the distant past were characterized by a childlike naivety, their knowledge dwarfed by the average elementary school child of the 21st century. If this indeed be the case, then surely we’ve become a species of supermen, right?

Yet doubts inevitably creep in, fermenting into an oppressive and all-pervading “sense of unease,” just as Makiguchi had described. Man was supposedly freed from the “invisible dangers” of the spirit world, yet he now contends with new intangible horrors in the form of countless mental maladies and increasingly inhuman techniques. Should he drift into unresolvable nihilism or attempt to drop out of society, the onslaught of technique marches on without rest regardless. In his current irreligious phase, man has seemingly forfeited his fate, leaving it to forces outside of his control and understanding; the cold revenge of the supra-rational.

The helplessness modern man feels in the face of this decaying future, or “sense of ending,” combined with the relatively dismissive view of the past elaborated above, has led to him, as Christopher Lasch writes, “losing the sense of historical continuity, the sense of belonging to a succession of generations originating in the past and stretching into the future.” Published in 1979, his book “The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations” explores this phenomenon and the myriad of effects that stem from it, noting a then-burgeoning fixation on the “self” as the primary characteristic of the new chronologically atomized human. He writes:

Indeed Americans seem to wish to forget not only the sixties, the riots, the new left, the disruptions on college campuses, Vietnam, Watergate, and the Nixon presidency, but their entire collective past, even in the antiseptic form in which it was celebrated during the Bicentennial. Woody Allen’s movie Sleeper, issued in 1973, accurately caught the mood of the seventies. Appropriately cast in the form of a parody of futuristic science fiction, the film finds a great many ways to convey the message that “political solutions don’t work,” as Allen flatly announces at one point. When asked what he believes in, Allen, having ruled out politics, religion, and science, declares: “I believe in sex and death — two experiences that come once in a lifetime.”

To live for the moment is the prevailing passion — to live for yourself, not for your predecessors or posterity.

Like Franco Berardi, Lasch saw the 1970s as the decade where the myth of perpetual human progress had begun to break down. While some of Lasch’s contemporaries suggested the apocalyptic tenor of the time to have a millenarian quality, this was far from the case. “It is the waning of the sense of historical time,” Lasch writes, “that distinguishes the spiritual crisis of the seventies from earlier outbreaks of millenarian religion, to which it bears a superficial resemblance.”

A prominent component of this is a total lack of any notion of a past “golden age” which can be returned to with the re-emergence of a “sleeping king.” When the past is nothing but comparative darkness, there can be no prior golden age. Nor can the future be trusted once the “march of progress” has died and the “end of history” has been rendered nonsensical. Moreover the climate is far more “therapeutic” than religious. “People today hunger not for personal salvation, let alone for the restoration of an earlier golden age,” Lasch states, “but for the feeling, the momentary illusion, of personal well-being, health, and psychic security.” Even religion is often converted into a form of therapy, as was the case with Buddhism’s Western techniciziation.

In this new desacralized age of pastless and futureless pessimism, man has no choice but to turn inward, displaying a “tendency to withdraw into thought,” as Makiguchi wrote. Man gazes upon the “self” rather than his place in a universe which has become increasingly hostile, and indulges in ephemeral fixations like consumerism, sensory pleasure, and fame as the highest possible achievements. The cosmos is reduced to the size of a pinpoint, filled with only the “individual” and his desires. This, of course, raises the stakes in the fulfillment of said desires, as a “self” only has one chance to be made manifest and be recognized. Lasch explains:

The modern propaganda of commodities and the good life has sanctioned impulse gratification and made it unnecessary for the id to apologize for its wishes or disguise their grandiose proportions. But this same propaganda has made failure and loss unsupportable. When it finally occurs to the new Narcissus that he can “live not only without fame but without self, live and die without ever having had one’s fellows conscious of the microscopic space one occupies upon this planet,” he experiences this discovery not merely as a disappointment but as a shattering blow to his sense of selfhood.

All of this inevitably produces derangement on a societal level, which Lasch characterizes as being in line with the profile of “narcissism.” He lists as a set of associated behaviors: “fear of old age and death, altered sense of time, fascination with celebrity, fear of competition, decline of the play spirit, [and] deteriorating relations between men and women.” This emerged alongside the technically-derived hyperreal inclination of post-industrial civilization, with Lasch noting the increased importance of spectacle and its hyperreal significance all the way back in the 70s:

The proliferation of recorded images undermines our sense of reality. As Susan Sontag observes in her study of photography, “Reality has come to seem more and more like what we are shown by cameras.” We distrust our perceptions until the camera verifies them. Photographic images provide us with the proof of our existence, without which we would find it difficult even to reconstruct a personal history… Among the “many narcissistic uses” that Sontag attributes to the camera, “self-surveillance” ranks among the most important, not only because it provides the technical means of ceaseless self-scrutiny but because it renders the sense of selfhood dependent on the consumption of images of the self, at the same time calling into question the reality of the external world.

In order to realize the newly all-important “self,” modern man clings to symbols and signals as proof of his “selfhood.” Virtue becomes something to be displayed, not to be acted out, and politics becomes a matter of “self-expression” and a way to gain recognition among one’s peers rather than a means to improve the lives of one’s fellow citizens. “Even the radicalism of the sixties served, for many of those who embraced it for personal rather than political reasons, not as a substitute religion but as a form of therapy,” Lasch writes. “Radical politics filled empty lives, provided a sense of meaning and purpose.”

Indeed, we saw this come to full fruition in subsequent decades with the technicization of supposedly “radical” left-wing political beliefs; absorbed and reconfigured by the forces of neoliberalism into hollowed-out pseudo-therapeutic consumer lifestyles, much to the ironic delight of self-avowed Leftists who were desperate to regain some semblance of a sense of victory, no matter how empty. Robbed of any coherent unifying theoretical foundation or historical narrative, Leftism is only truly identifiable as a psychological profile, one which becomes more deranged and self-destructive as it is unmoored from all ideological coherence and refocused onto the hyperreal.

The derangement itself is often integrated into the technical milieu and wielded in furtherance of its aims, a phenomenon we often see in modern political activism, yet this state of affairs cannot perpetuate itself in the face of inevitable widespread demoralization and the exhaustion of legacy social infrastructure. It must break down to be reconfigured into new mechanisms, a process I believe to be underway at this very moment. In the meantime, we are experiencing an era of managed decline which we are seemingly unable to address in any meaningful way for fear of damaging the systems and narratives we’ve spent so much time cultivating; dying pseudo-religions lash out as they sink to the dismal realm of Hades, attempting to pull down with them anything within their reach.

We’ve thus been left with a sense of “reality” that is not only devoid of anything sacred and transcendent, but cannot even observe its immediate material circumstances, instead being constantly spirited away into the technological unreal; mere ghosts of the concrete world. Jacques Ellul writes:

When [the average man] leaves his job, his joy in finishing his stint is mixed with dissatisfaction with a work as fruitless as it is incomprehensible and as far from really productive work. At home he “finds himself” again. But what does he find? He finds a phantom. If he ever thinks, his reflections terrify him. Personal destiny is fulfilled only by death; but reflection tells him that for him there has not been anything between his adolescent adventures and his death, no point at which he himself ever made a decision or initiated a change.

However, I would say that even death is rendered hyperreal these days, characterized not by the passing of a life, but by its propagandistic utilizations: “but what does the death say about society?” We can’t even die without our corpse being fed into the cold iron jaws of human technique, digested into a temporary symbol of something or other before expending its usefulness and being swept away with so much other digital detritus.

Man lives neither for divine truth and righteousness, nor necessarily for the betterment of material conditions for his posterity, but for the hyperreal and the furtherance of technique. We have been drawn down not to the most baseline sensory understanding of reality, but to something underneath it; the realm of the mechanical phantom.

But if this is our state of affairs, what alternatives do we have? How did time come to be subjugated, and how exactly did man of the past experience time before the continuum was ripped from him? Most importantly, what role should the ancient wisdom found in religions play in human civilization going forward? Should we continue viewing men of antiquity as naive rubes, or did they really hold something important which was discarded in our quest to attain new technological heights? If we are to go about answering these questions, we must first do away with modern prejudices around the ancient world and try to see things from a very different perspective. In service of this, I will outline several views of time throughout this volume which push against our current shattered understanding.

Chapter 12: The Subjugation of Time

“Money’s flesh.

Money is flesh in your hand.”

-Swans, from “Money is Flesh”

We currently live in an age of growing pessimism. With “the end of history” and “march of progress” narratives now on life support, the future, in the eyes of many, holds untold horrors of steel and smoke, snarling and foaming at the mouth and waiting to be unleashed upon a soft and unprepared populace. What once held so much hope several decades ago has in recent history descended into visions of bloody dystopia. “The future is over,” writes Franco Berardi. “It is not a new idea, as you know: born with punk, the 1970s and ’80s witnessed the beginning of the slow cancellation of the future. Now those bizarre predictions have become true.”

Francis Fukuyama, in his book “The End of History and the Last Man,” paraphrased Alexandre Kojeve, stating that “after the rise of the Shogun Hideyoshi in the fifteenth century, Japan experienced a state of internal and external peace for a period of several hundred years which very much resembled Hegel’s postulated end of history.” To Fukuyama and Kojeve, such a time of peace, characterized in the historical record by the many artistic achievements of the era, was a preview of a golden age to come. What Fukuyama fails to mention, however, is that many in the Edo period saw it as an age of decline and, much like we often do now here in the West, frequently looked to the past for answers. One man’s “end of history,” it seems, is often another man’s decadence.

The Zen Master Suzuki Shosan was one of these individuals. His book of sayings records a conversation he had with one of his disciples, who had claimed that the era’s monks had “no interest in The Way.” Shosan replied: “Quite apart from that, not one of them actually leaves the world at all. That’s why if you threw them out of their temples right now they’d all be helpless.” In his eyes, the Buddhist clergy had been drained of all vitality and contented themselves with “skinning the dead” to get by, i.e. merely conducting funerary services in exchange for money. “Still less does anyone work up the grit to sink his teeth into things like a man-eating dog,” he continued. “It’s too bad, it really is.”

The most significant instance of this, however, were the Kokugaku scholars, who generally saw the remote past of Japan as the peak of societal harmony. An example from the prominent scholar Motoori Norinaga can be found in his treatise on ancient poetry entitled “Ashiwake Obune.” Per John R. Bentley’s “Anthology of Kokugaku Scholars”:

Simply because these people lived in the ancient past does not mean that they were all honest, and there were no people who were deceitful to some extent. Even among the ancient people there were many who were full of wickedness, lies, and deception. Even in the present we find that there are some people who are quite sincere and simple, so one cannot make blanket statements about people. However, if you compare the overall characteristics of the ancient past with the present, anyone will notice the change.

Norinaga’s contemporary, Kamo no Mabuchi, had even stronger thoughts on the matter, believing that the ancient Japanese developed no writing system because it was not needed. People were honest and communicated clearly, and what they communicated, they remembered. To appreciate only the eras after Chinese writing was put to use and dismiss the eras before as childish and naive was, to him, like “wishing to scoop up water at the muddied end of the river, hating the upper stream where the water is clear.” He writes in his treatise “Goiko”:

As I have said early on, the original hearts of the Japanese were sincere, so there were few tasks and few words; there was no confusion in speech, and people did not forget what they had once heard. If there was no confusion in communication, and nothing was forgotten in that era, then the ancients should have transmitted their traditions for a long time. Since the hearts of the people were straightforward, there were few edicts from the emperor. And when the court gave an imperial edict, it spread throughout the land like the wind, penetrating the hearts of the people like water.

Since this was the case, heaven caused the population to increase, and there were no mistakes in the orally transmitted traditions. The pure people protected the traditions for many generations, nothing varying. What need did the ancient Japanese have for characters?

But he did not extend this belief to the Japanese alone. In his work entitled “Kokuiko,” he says that “when one reads the words of Laozi, you realize that the hearts of the Chinese originally were sincere. They were sincere like the poetry of the ancient Japanese…” However, later developments would render China an “evil-hearted country,” with their “deep and profound teachings” appearing outwardly reasonable, but working to throw the country “into confusion.”

Mabuchi’s words evoke an image of the past that was “pure” and uncorrupted by the complications of words and philosophies. In the eyes of the Kokugaku scholars, the lives of those in the remote past was characterized by a simple sincerity which required few words to express itself. Humans of later eras, on the other hand, became increasingly enamored with words and pretentious doctrine, and thus required more complexity, regulation, and long-winded philosophy. “False wisdom,” in the belief of men like Mabuchi, had captured men’s hearts and “polluted” their minds.

Whether or not we take this as true is irrelevant for my purposes at the moment. The important point is that it illustrates a view of the past that was seen as very naive and foolish for much of modern history, especially in the Western world, but is now seeing a resurgence as technological advances paint for us a future that looks increasingly less human. It is, in essence, an inversion of the “march of progress” narrative; one which looks to the past longingly rather to a theoretical “end of history.”

A disdain for the Edo period was also shown by the Nichirenist thinkers of the early 20th century, although for a different reason. Despite being a largely Buddhist movement, they saw the Meiji revolution (which had devastated the Buddhist establishment through a wave of widespread iconoclasm) as an extremely positive development, as it shattered the utterly stagnant religious environment of the Edo era and freed Buddhist thought from its secularized and bureaucratized confines. Kishio Satomi writes in his book “Discovery of Japanese Idealism”:

After the death of Nichiren, spiritual Japan had to pass through a lifeless period of monotony and stagnancy for about six hundred years. At the close of this period, the darkness was suddenly pierced by the appearance of the most prominent idealist, the late Emperor Meiji the Great.

In Satomi’s eyes, and those of his father, Chigaku Tanaka, the Meiji era was a step towards realizing Nichiren’s vision of worldwide proliferation of Lotus Sutra Buddhism; the catalyst to an eventual end to the “Latter Age” and period of decrease wherein man experiences the three calamities of war, famine, and pestilence. Satomi explains the Nichirenist interpretation of Nichiren’s writings in his book “Japanese Civilization: Its Significance and Realization” as follows:

According to Nichiren, in the degenerate days of the Latter Law, there is no Buddhist commandment outside of our vow for the reconstruction of the country and the realization of the Heavenly Paradise in the world. Even the so-called virtuous sage, if he does not embrace this great and strong vow, in other words only enjoys virtue individually, such a sage is pretty useless.

To fully comprehend the Buddhist concepts of the Latter Age and period of decrease, however, we must return to the oldest model of time, namely the “cyclical.”

Time, in the eyes of ancient man, was characterized by repetition; day and night, the changing of the seasons, birth and death. Thus the “cycle” was the most natural model of cosmic time. The Aztecs saw their world as being subject to “sun cycles” wherein the sun itself would fall and need to be reborn, while the Hindus saw the cosmos through the lens of a “yuga cycle” consisting of four periods: the Satya Yuga, Treta Yuga, Dvapara Yuga, and Kali Yuga. Buddhists as well saw time as a holographic expanse of various cycles of degradation and restoration, but we will discuss that in far more depth in a later chapter.

According to the Marxist thinker Guy Debord, however, the dominance of cyclical time began to slip with the popularization of writing and the creation of historical chronicles. In his view, this nascent “linear” model of time was determined by the masters of the respective societies, thus “history’s” direction was a product of whoever was in charge of the recordings; the “owners” of time. Debord writes:

The chronicle is the expression of the irreversible time of power. It also serves to inspire the continued progression of that time by recording the past out of which it has developed, since this orientation of time tends to collapse with the fall of each particular power and would otherwise sink back into the indifferent oblivion of cyclical time (the only time known to the peasant masses who, during the rise and fall of all the empires and their chronologies, never change).

However, Debord states that it was not until the “monotheistic” religions rose to prominence that linear time was ushered in as a defining fixture of the human experience by establishing a sort of compromise “between the cyclical time that still governed the sphere of production and the irreversible time that was the theater of conflicts and regroupings among different peoples.” These faiths are at least in part defined by an orientation towards a singular future event, which Debord summarizes as “the Kingdom of God is coming” (I want to note here that linear-time is not exclusive to the monotheists, but we will cover that in due time).

The eventual recession of religious thought and rise of industry marked the true solidification of continuous linear time in the form of what Debord calls “the irreversible time of production.” He writes that “the victory of the bourgeoisie is the victory of a profoundly historical time, because it is the time corresponding to an economic production that continuously transforms society from top to bottom.” History was, in effect, established “as a general movement — a relentless movement that crushes any individuals in its path.” Yet there is a caveat: most of society, although instilled with an understanding of linear historical time, is “prevented… from using it. ‘Once there was history, but not any more.’”

The last sentence in the quotation above calls to mind Francis Fukuyama’s claims about “the end of history” having been reached with corporatized Liberal Democracy, and such a narrative can indeed be seen as one form which the subjugation of time can take; rendering man a mere spectator of his own overarching history while handing him over to a fractured conception of time, which is overwhelmingly colored by his field of employment. The average worker in America thus sees his perception of time split into work days, weeks, quarters, years, and pay periods, all with different transactional implications; e.g. “annual bonuses,” “vacation time,” “quarterly performance reports,” etc. The economy as a whole too works in business cycles, boom and bust cycles, annual cycles, and so on.

This deranged iteration of cyclical existence feeds into what blogger Paul Skallas calls “the consistency space,” the tendency to strive towards keeping things frozen as they are for as long as possible, stuck in the same “work cycle” indefinitely. He writes in a blog post entitled “The 4-Hour Life”:

… your real job is to be consistent at work. To be reliable. You’re in a domain called the Consistency Space. A domain where messing up could cost you your nice life. It’s not about scoring goals as much as not letting goals into the net. This simple idea influences your life, and the lives of others. It is the single most influential idea around you…

Mondays feel like Mondays, Fridays feel like Fridays, nothing you can do will change that. The structure will dictate how we feel, in a way that grey clouds make us feel slightly more low energy than a sunny day.

When we also take into account the fact that various technical fields can have very different ways of viewing time, for instance accounting and politics (election cycles, tax periods, etc), then what we have overall is a system in which every individual has their own miniature conception of time, often completely separate from those who do not work in the same field or for the same company. Like everything else, time has become atomized and individuated; a “self-time,” if you will, turning one’s view away from the world at large and further inward until he finds it difficult to even communicate with others. How can you relate to someone who resides in a completely different world?

The unifying feature between all of these various “self-times,” of course, is the clock; mechanized time. Man is obsessed with time; constantly running late for this and that and peering towards that infernal machine hanging on his office wall. He is, after all, paid for his time, or rather he sacrifices his time, and thus his life, to make a living; his time is money, and “money is flesh.” There are also entire industries built around wasting people’s time, like advertising. If a man will not willingly trade his attention (i.e. his processing power, “cyber-time”), there are techniques for ripping it away through other means.

Countless individuals, countless information streams, all pour into man at any given time, fighting for a bloody pound of his very finite “cyber-time,” and the pressure strains his entire being. Here we see what can be called “commodified time.”

Like this, time has not only been shattered, but utterly subjugated. Time is differentiated for each person because that is the optimal model of time for technological neoliberal society, feeding into what Jacques Ellul called “the plasticity of the social milieu.” Atomization, more than anything else “conferred on society the greatest possible plasticity — a decisive condition for technique.” The “self-time” I have described is thus a “technicization” of time, broken into countless modular pieces for the benefit of technical furtherance.

With all of this in mind, is it any wonder that the future has become so overwhelmingly bleak? How could it be any other way?

Upon examining the array of frameworks developed for the understanding of time, the early 20th century French philosopher and metaphysician Rene Guenon (who was, as you will find, quite different from Marxists like Debord) saw “cyclic time” as the most accurate by far, writing in his 1945 book “The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times” that “time is not something that unrolls itself uniformly, so that the practice of representing it geometrically by a straight line, usual among modern mathematicians, conveys an idea of time that is wholly falsified by over-simplification… The correct representation of time is to be found in the traditional conception of cycles, and this conception obviously involves a ‘qualified’ time.’”

To understand what exactly is meant by the peculiar passage above, we will need to explore the profound and perhaps somewhat disturbing notion that Guenon introduces (or rather re-introduces, if we are to accept that the cyclical view of time is in fact the oldest) in his aforementioned book of time having a “quality” on top of having a “quantity.” Before that, however, we should establish the scope of what is meant by the term “quality.”

Chapter 13: Material and Time (or “The Curse of Prometheus”)

“You’ll hear me now, you demigods…

Either let me go or put me in the dirt.”

-HEALTH, from “Demigods”

The ancient Greek poem “Works and Days,” written by Hesiod and addressed to his brother Perses, dedicates a chapter to describing five different ages, in each of which live a different “race” of man. These can be enumerated as follows:

The Golden Age

The Silver Age

The Bronze Age

The Heroic Age

The Iron Age

According to Hesiod, the first of these ages was the best, as the golden race was free from toil and strife and “lived like gods without sorrow of heart.” After their passing came the silver race, who was “less noble by far,” although still lived with relatively little sorrow. Hesiod states that this race was “put away” by Zeus because they would “not give honour to the blessed gods who live on Olympus.”

Third came the bronze race, which was “in no way equal to the silver age, but was terrible and strong.” The bronze men had “adamantine” hearts and fearsome strength. “Great was their strength and unconquerable the arms which grew from their shoulders.” They also had a taste for violence and war, thus their age was eventually done away with by their own hands and “passed to the house of Hades.”

Next came the race of heroes or “demi-gods,” who were “nobler and more righteous, a god-like race of hero-men… the race before our own.” These men surpassed both of the generations before them, venerating the gods of Olympus while also exuding incredible strength and will. Although some lost their lives to conflict, many survived and eventually retired to “the ends of the Earth” where “they live untouched by sorrow in the islands of the blessed along the shore of deep swirling Ocean, happy heroes for whom the grain-giving earth bears honey-sweet fruit flourishing thrice a year, far from the deathless gods, and Cronos rules over them; for the father of men and gods released him from his bonds.”

In his verses concerning the age in which he and his brother supposedly lived, the altogether inferior “Iron Age,” Hesiod writes the following lament:

Thereafter, would that I were not among the men of the fifth generation, but either had died before or been born afterwards. For now truly is a race of iron, and men never rest from labour and sorrow by day, and from perishing by night; and the gods shall lay sore trouble upon them. But, notwithstanding, even these shall have some good mingled with their evils. And Zeus will destroy this race of mortal men also when they come to have grey hair on the temples at their birth.

The father will not agree with his children, nor the children with their father, nor guest with his host, nor comrade with comrade; nor will brother be dear to brother as aforetime. Men will dishonour their parents as they grow quickly old, and will carp at them, chiding them with bitter words, hard-hearted they, not knowing the fear of the gods.

The Iron Age, according to the above account, is characterized by much weariness and suffering; by the shackling of man to his work and the splintering of social relations. Work, in this sense, is the burden of our inferior “race” with which we are forced to constantly contend until our lives are shortened (“for in misery men grow old quickly”) and we are “destroyed.”

“For the gods keep hidden from men the means of life,” Hesiod states.

This in itself is not inconsistent with other beliefs around eons of decline, which were common among ancient civilizations. However, what I find particularly interesting about the framework presented by Hesiod is that four of the five ages are named after metals. They are not necessarily bestowed these titles because the respective metals are the primary materials wielded by the “races” in pursuit of civilizational advance (although this does seem to be the case with both the bronze and iron ages), rather there appears to be a quality assigned to these substances which does not necessarily correlate to their purely physical properties.

After all, it’s said that Prometheus brought work to mankind when he bestowed upon them the power of flame, and there was no application of fire more advanced, and therefore potentially terrifying, than the transformation of metals into the tools of men. In fact, it seems an undeniable tendency for man to become enslaved to the very tools he makes; every technological leap resulting in new and more advanced ways for him to kill and be killed, and new modes of production which, although able to increase productive output several times over, never truly liberate him from his eternal affliction.

Man, in this sense, is destined to the same cruel fate as Prometheus, to forever give over his body in pieces as part of some divine punishment. For Prometheus, it was his liver. For us, it is our time, energy, and health. This goes on for countless ages, repeating itself over and over again, until all energy and will is exhausted and man himself is worn down by his own machinations; victim to his own lofty ambition. As Franz Kafka writes: “Every one grew weary of the meaningless affair. The gods grew weary, the eagles grew weary, the wound closed wearily…”

It is perhaps due to this perspective that the Greeks did not advance in the realm of technique as much as one may suspect. In “The Technological Society,” Jacques Ellul outlines the distrust the ancient Greeks seemed to have for technological advance, writing:

For one thing, theirs was a conception of life which scorned material needs and the improvement of practical life, discredited manual labor (because of the practice of slavery), held contemplation to be the goal of intellectual activity, refused the use of power, respected natural things. The Greeks were suspicious of technical activity because it represented an aspect of brute force and implied a want of moderation.

But we should not make the mistake of attributing such an attitude to the Greeks alone. Indeed, a distrust of the use of metal in particular was common to ancient peoples, with Rene Guenon making special note of the ancient Hebrews in his book “The Reign of Quantity”:

… from the beginning of the time when the use of stone was allowed in special cases, such as in the building of an altar, it was nevertheless specified that these stones must be ‘whole’, for ‘you shall lift up no iron tool upon them’; according to the precise terms of this passage, insistence is directed not so much to the stone being unworked as to no metal being used on it: the prohibition of the use of metal was thus more especially strict in the case of anything intended to be put to a specifically ritual use. Traces of this prohibition still persisted even when Israel had ceased to be nomadic and had built, or caused to be built, stable edifices…

The Japanese too seemed to hold a certain distrust of metal, which was also associated either with war and work or with religion (it’s worth noting that metalworking advanced significantly in the Asuka period, around the same time as Buddhism’s generally-accepted introduction to the island nation). Thus iron was most heavily associated with farming tools and weapons, while bronze was often used to create sacred objects like mirrors and Buddha icons.

This dual nature of metal is reflected in their mythology as well, with the powerful flame god Hi no Kagutsuchi depicted as a deity of both creation and destruction. When he was dismembered by his father, Izanagi no Mikoto, his blood droplets instantly brought forth other deities, including the important martial god of blades and thunder, Takemikazuchi, also known as the God of Kashima.

However, his birth resulted in the death of his mother, Izanami no Mikoto, who descended to the underworld where her still-animated corpse gave birth to demons. Here we can see the “equal and opposite” nature of creation at play. Prometheus brought humans fire and work, while Izanami no Mikoto brought creation and destruction, both blossoming forth in a wreath of terrible flame. Make no mistake, the curses bestowed onto us by Prometheus and through Kagutsuchi continue to this day.

[Note: I discuss Hi no Kagutsuchi in the second chapter of my work “The Mad Laughing God,” which you can read in the appendix.]

It is also a severely underexamined fact that the syncretic Japanese deity known as “Konjin” is a god of metals. Transmitted via the Taoism-adjacent doctrines and practices of Onmyodo during the Heian era, Konjin was considered to be an itinerant deity, i.e. one who would be associated with different directions over time, thus lending the particular directions he occupied a sinister quality that could cause misfortune. It can be observed here that it was not just the element that the Onmyoji considered to have non-observable quality, but “space” as well, and this quality would change with the gradual shifting of the stars and planets.

The effects of Konjin’s occupation were strongest when he was in either of the “demon gates,” which are in the Northeastern and Southeastern directions. These directions were (and sometimes still are) considered fairly inauspicious regardless of which deity occupied them, and even today you can still find small guardian icons adorning shrine and temple buildings on their northeastern corners.

Why exactly the god of metals was considered so fearsome among the itinerant gods in Onmyodo is not exactly clear to me, but it is worth mentioning that another notorious directional god named Daishogun (literally “Great General”) was associated with the planet Venus along with Konjin, a detail which may be a clue to unraveling the mystery. Planetary spirits being linked to metals is, according to Rene Guenon, nothing new. He writes in “The Reign of Quantity”:

… it must be remembered in the first place that the metals, by reason of their astral correspondences, are in a certain sense the ‘planets of the lower world’; naturally therefore they must have, like the planets themselves, of which they can be said to receive and to condense the influences in the terrestrial environment, a ‘benefic’ aspect and a ‘malefic’ aspect.”

Indeed, we see this as a recurring theme in both Chinese and Japanese iterations of Taoism and in Western alchemical frameworks, and should it be too surprising when we consider the metallic composition of meteorites? There are also tales in the Nihon Shoki and passed down through Omika Shrine tradition of the chaotic deity Amatsu Mikaboshi, who was subjugated by the aforementioned martial god Takemikazuchi and two others. It’s claimed by Omika Shrine that part of Amatsu Mikaboshi’s soul then fell to Earth to be sealed away in a stone currently located on their grounds.

Regardless, it’s clear that there is a certain alien quality attributed to metals that isn’t prominent for any other conventional building material, one which transcends the mere sensory qualities with which modern scientific measurement concerns itself. Guenon posits a potential civilizational source for this understanding: At the dawn of humanity, the primary modes of living were nomadic and agricultural, a duality we can see reflected in the biblical story of the brothers Cain and Abel. Nomadic societies like the very early Hebrews rarely used stone due to the necessity of mobility, while those who took up agriculture utilized stone to a more significant degree (but, of course, no metals until later eras). Life in a “town” represents a more advanced form of agricultural society, one that uses stone far more than the two previously mentioned lifestyles. Guenon writes:

… minerals, in their commonest form, that of stone, are principally used in the construction of stable buildings; a town, considered as the collectivity of the buildings of which it is made up, appears in particular as something like an artificial agglomeration of minerals; and it must be reiterated that life in towns represents a more complete sedentarism than does agricultural life, just as the mineral is more fixed and more ‘solid’ than the vegetable.

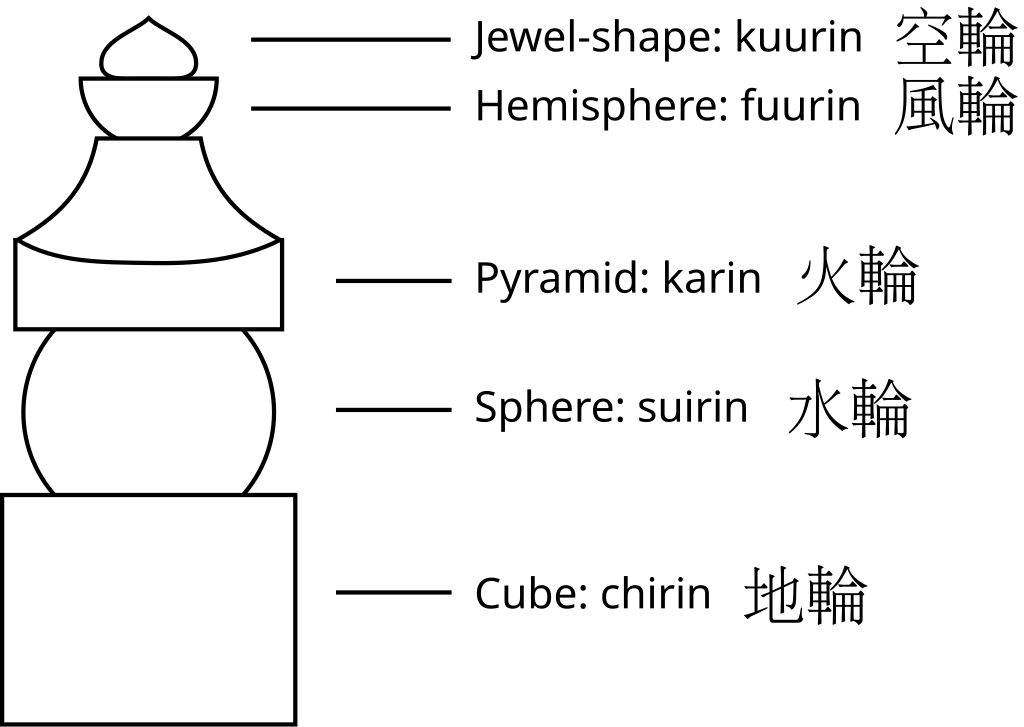

In this narrative we can witness what Guenon would call the “solidification” of human life, one which roots it into a more fixed and materially-focused mode of existence, something that he considers a “downward movement” towards a lower level. Indeed, we can see this at play in the Buddhist five-level pagodas of Japan, which are composed of five shapes representing both the five esoteric Buddhas and the five elements:

Jewel - Space

Half-circle - Air

Pyramid - Fire

Sphere - Water

Cube - Earth

The two extremes of the above framework, space and earth, are embodied in Mahayana mythology in the brothers Ksitigarbha (literally “Earth Matrix”) Bodhisattva and Akasagarbha (“Space Matrix”) Bodhisattva. Ksitigarbha is portrayed as a purely compassionate being who descends to the deepest and darkest depths of hell in order to bring the sinners suffering there back up to the higher realms, while his counterpart, Akasagarbha, oversees the Buddhist practitioners and sages looking to transcend their material existence and seek out supreme realization of ultimate reality (it is, in fact, he who Japanese Mahayanist monks have historically been asked to confess their misdeeds to). The “upward” movement implied here is quite apparent.

It’s logical that the most stable, or “solid,” of the above elements would occupy the bottom slot in the five-shape pagoda, while the least solid, namely “space,” that which most accurately illustrates Buddhist notions of “emptiness,” would be at the very top. Something which may be apparent by now is that metal is entirely absent from this formulation, although it is likely included within the “Earth” segment by default. Should it be rendered separate, however, it would likely be further underneath.

[Note: Metals, most notably iron, are very often referenced in description of Buddhist hells, with a very prominent example being Ksitigarbha’s description of Avici, or “Relentless/Incessant Hell,” in the “Original Vows of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Sutra,” an excerpt from which is reproduced below:

In regard to the Incessant Hell, this city of hells is more than eighty thousand li in perimeter. The city walls are made entirely of iron, ten thousand li in height. Atop these walls the mass of fire leaves hardly a gap. Within this city of hells, the various hells are interconnected, each with a different name. There is just one hell named Incessant. It is eighteen thousand li in perimeter. Its hell walls are a thousand li in height, all made of iron, and with flames at the top reaching to the bottom and flames at the bottom reaching to the top. Iron snakes and iron dogs spew fire and rush here and there in pursuit atop these hell walls.

The significance of metal’s prominence in the low reaches of Buddhist hell is something I have not seen explained by any of the Buddhist writings I have examined. Perhaps it is yet to be made clear through the developments of human civilization, placed in the texts in anticipation of a far later age. Some food for thought.]

It should be stated that the Buddhists considered none of the elements inferior to the others, despite their placement in the memetic frameworks covered thus far, but they were still endowed with their own qualities which extended beyond their mere physical properties. We already know that the way in which we construct our tools has profound material effects on all other areas of life. Should we be so bold as to expect that changing the materials from which our civilizations are constructed wouldn’t also affect us in less tangible (one could say “spiritual”) ways?

We can already recall all of the ways in which our lives have been guided by the material consequences of metallic domination: the rise of the machine and subsequent usurping of the throne by its offspring “technique,” the dramatic increase in production of consumer goods and thus development of Consumerism and its “consumption-based identities,” and ultimately the mass desacralization of society. However, even metal seems to be on its way out as the material of choice for humanity, replaced by even more alien substances.

Plastic, a now ubiquitous material for consumer goods, has become a symbol of artificiality in the minds of many. It is not found in nature, but concocted in laboratories and factories, and it does not degrade like more natural materials do. Yet it is also cheap and plentiful, so plentiful that we have no idea how to get rid of it when the need arises, and it now accumulates in our bodies, altering our chemistry in ways that we have yet to fathom. What the spiritual qualities could be of such a substance is anyone’s guess, but I highly doubt they would be “benefic.”

Just as impactful is the rise of the digital, which is the next step in the societal utilization (or one could say “technicization”) of metal. While not tangible in the same way as the four/five elements of Japanese spirituality expounded above, we can see that it does have intangible qualities of its own which are currently wrecking havoc on modernity. For instance, it’s no longer a secret that the digital tends towards monopolization, just as “technique” does in general.

Because of this, we have been steadily moving towards a form of technological economic feudalism as a replacement for the more conventional “Capitalism,” inextricably intertwining the technological oligarchy with the governments. If you want to even start a tech company, it’s inevitable that you will deal with “big tech” and its utter stranglehold over the technological sphere, “renting” digital spaces from them and buying their countless digital goods and services. Many small companies even end up getting purchased by the “big tech” companies as a way to further stifle any burgeoning competition and solidify their monopolistic reign.

The digital has invaded our homes in the form of cameras and “home assistants,” as well as our minds through the many forms of entertainment media and advertising. It spies on our personal lives through social media posts and advanced information-gathering techniques, and psychologically analyzes us to the utmost degree through its inscrutable algorithms. With the advent of LLMs and other forms of generative artificial intelligence, it also may conquer the “spiritual,” but we will explore that in more detail in a later chapter.

Sure, it may be possible to retreat from the technological onslaught to a certain extent, but human civilization and even the very face of the Earth have changed so significantly in accordance with the wild winds of technique and the machine that a complete purposeful regression is impossible. “For example, consider motorized transport,” Theodore Kaczynski writes in his manifesto, “Industrial Society and its Future.” He continues:

A walking man formerly could go where he pleased, go at his own pace without observing any traffic regulations, and was independent of technological support-systems. When motor vehicles were introduced they appeared to increase man’s freedom. They took no freedom away from the walking man, no one had to have an automobile if he didn’t want one, and anyone who did choose to buy an automobile could travel much faster and farther than a walking man. But the introduction of motorized transport soon changed society in such a way as to restrict greatly man’s freedom of locomotion. When automobiles became numerous, it became necessary to regulate their use extensively. In a car, especially in densely populated areas, one cannot just go where one likes at one’s own pace. One’s movement is governed by the flow of traffic and by various traffic laws. One is tied down by various obligations: license requirements, driver test, renewing registration, insurance, maintenance required for safety, monthly payments on purchase price.

Moreover, the use of motorized transport is no longer optional. Since the introduction of motorized transport the arrangement of our cities has changed in such a way that the majority of people no longer live within walking distance of their place of employment, shopping areas and recreational opportunities, so that they HAVE TO depend on the automobile for transportation. Or else they must use public transportation, in which case they have even less control over their own movement than when driving a car. Even the walker’s freedom is now greatly restricted. In the city he continually has to stop to wait for traffic lights that are designed mainly to serve auto traffic. In the country, motor traffic makes it dangerous and unpleasant to walk along the highway.

Here, the principles we’ve discussed come into clear view. What was once meant to liberate man has instead rendered him a slave to that previously promised liberation. He hammers iron and bends it to his will, only to find after the fact that he has forged his own chains, and now wears them in perpetuity. Such is his curse, which manifests itself time and time again as the ages pass, in accordance with the materials he wields in service of his whims. Is it any wonder that a man like Kaczynski eventually cracked under the weight of this grim realization, just as many men before him surely have?

Considering all we have covered here, it’s overwhelmingly evident that different substances can be considered to have different “qualities,” whether you want to take into account just the material aspects or the spiritual as well (which you certainly should, for reasons which will become abundantly clear later). If we accept this as true, then we can move on to the next step and apply the same principle to the element of “time.”

Chapter 14: The Quality of Time (and its Dissolution)

“It’s always out there, just past the 7-11, around the cloverleaf… the darkness that waits for me. Can’t see it unless I turn away. It’s not there when I don’t look. Waits for me to come back. Waits for me to come sink in. Just waiting…”

-Information Society, from “Closing In”

The end of the 19th century saw theoretical physics enter into a moment of crisis around the properties of light. One of the men responsible was James Clerk Maxwell, who believed, along with other scientific thinkers of the 19th century, that light waves were propagated through some kind of material ether. However, as Thomas Samuel Kuhn writes in his book on “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” Maxwell’s own electromagnetic theory of light “gave no account at all of a medium able to support light waves, and it clearly made such an account harder to provide than it had seemed before.”

Maxwell’s theory was initially met with skepticism for this reason, but as it proved proficient in its predictive abilities, it “achieved the status of a paradigm” and “the community’s attitude toward it changed.” Yet the problem of the ethereal component still remained a thorn in the side of theoreticians. Kuhn continues:

The years after 1890 therefore witnessed a long series of attempts, both experimental and theoretical, to detect motion with respect to the ether and to work ether drag into Maxwell’s theory. The former were uniformly unsuccessful…

The puzzle remained unsolved until the introduction of Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity in 1905, which rendered the ether aspect to light’s travel unnecessary and dramatically changed the way physicists saw both space and time (now collectively called “spacetime”), recontextualizing them as “relative,” i.e. they would act differently depending on the mass, positioning, and velocity of the bodies in question. Bodies “warp” or “curve” spacetime, causing gravity (and therefore movement) as well as a shift in the way light is observed and time is experienced.

The last of the above effects is perhaps the most difficult to wrap one’s head around, as it implies that time itself changes depending on a body’s speed or the strength of gravitational force acting upon it slowing down with the increase of either. As one would expect, scientists eventually put this theory to the test when they had devised the means to do so, with one such effort now called the “Hafele-Keating experiment.”

In 1971, Joseph Hafele and Richard Keating, intent on exploring this supposed “clock paradox,” placed four atomic clocks onto regularly scheduled commercial airplane flights. The general concept behind the experiment was simple: first they would fly the clocks around the world in the Eastern direction, the direction of the Earth’s rotation, and measure the change in time against the stationary clocks at the United States Naval Observatory. Next, they would repeat the process, but instead fly the clocks Westward, against the Earth’s rotation. A 1971 Time Magazine article on the experiment, entitled “A Question of Time,” recounts the theory behind it as follows:

The paradox, which stems from Einstein’s 1905 Special Theory of Relativity, is difficult for the layman to comprehend and even harder for scientists to prove. It means that time itself is different for a speeding automobile, for example, than for one parked at the curb. The natural vibrations of the atoms in the engine of the moving auto, the movement of the clock on the dashboard and even the aging of the passengers occur more slowly than they do in the parked car. These changes are imperceptible at low terrestrial speeds, however, and according to the theory become significant only when the velocity of the moving object approaches the speed of light.

According to the paper study eventually published in the journal “Science,” the results of the airplane experiment were “in good agreement with predictions of conventional relativity theory.” It continues:

Relative to the atomic time scale of the U.S. Naval Observatory, the flying clocks lost 59±10 nanoseconds during the eastward trip and gained 273±7 nanoseconds during the westward trip, where the errors are the corresponding standard deviations. These results provide an unambiguous empirical resolution of the famous clock “paradox” with macroscopic clocks.

Indeed, it appears that, just as Einstein had predicted, time was relative depending on the conditions, or one could say “quality,” of the fabric of spacetime. Considering this startling discovery, what else could there be to learn about time? Could there perhaps be other “qualities” which we are overlooking due to a collective lack of perceptive ability? The French metaphysician Rene Guenon would say “yes.”

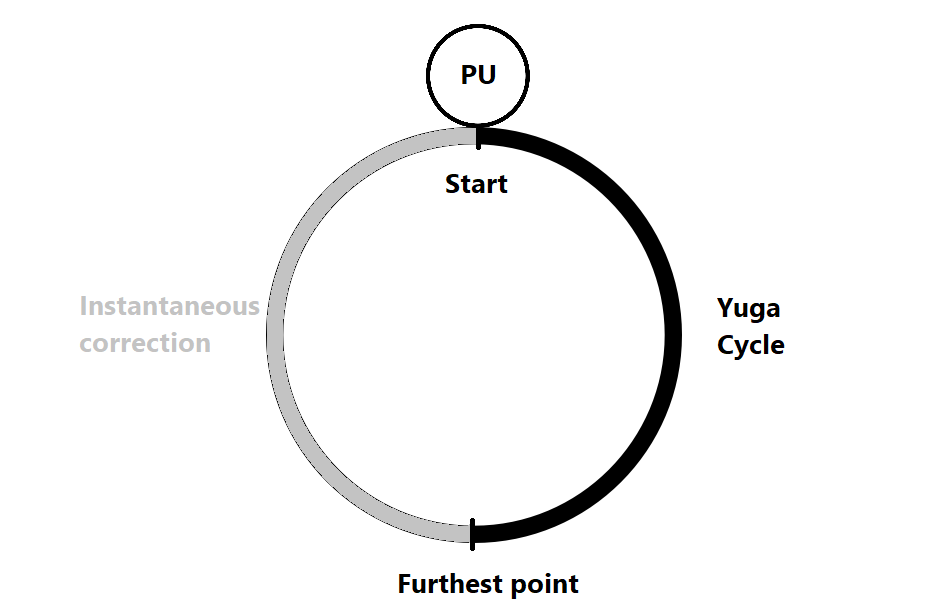

If we accept the circular model of time, as discussed in previous chapters, as well as the notion that time is relative, then the logical conclusion is that time itself could potentially change in quality depending on one’s position in a cosmic macrocycle. “According to the different phases of the cycle,” Guenon writes, “sequences of events comparable one to another do not occupy quantitatively equal durations.” This essentially means that the last phases of a cosmic cycle would unfold with higher rapidity. Guenon elaborates using Hindu doctrine as his example of choice:

… this is particularly evident in the case of the great cycles, applicable both to the cosmic and to the human orders, the most notable example being furnished by the decreasing lengths of the respective durations of the four Yugas that together make up a Manvantara. For that very reason, events are being unfolded nowadays with a speed unexampled in the earlier ages, and this speed goes on increasing and will continue to increase up to the end of the cycle…

The above-mentioned decrease in lengths for subsequent cycles is described in a footnote as “known to be proportionate to the numbers 4, 3, 2, 1,” meaning that the first part of the “yuga cycle” is four times longer than the last (the “Kali Yuga,” in which we are said to currently reside). This is not an instant shift, of course, rather it is an effect that Guenon believes to unfold gradually, like “the movement of a mobile body running down a slope and going faster as it approaches the bottom.”

In this illustration, what the “mobile body” is theoretically retreating from at the top of the hill is termed the “principal unity” by Guenon, and can be conceived of as the ultimate source which all traditional spiritual pursuits strive to realize, thus the cycle is characterized as a downward movement away from a supreme primordial unity. This movement terminates at the furthest point, when time has been condensed into a single moment, and the process rectifies itself instantaneously; a sudden “inversion of the poles,” like an hourglass being flipped over.

We can craft another illustration of Geunonian cyclical time using the Theory of Relativity as a guide by picturing a circle with the “principal unity” (PU) occupying the top end. The four divisions of the yuga cycle would be represented by the first half of the circle, while the instantaneous correction is represented by the second half. Thus the end of the cycle would actually occur at the point furthest from the principal unity, time speeding up as the cosmic location drifts away from what can be viewed as the spiritual gravitational pull of the principal unity.

It must be clarified, however, that this is not an objective description of how this metaphysical process works, but rather a visual model for understanding the principles that Guenon laid out in his text. The truth is that we cannot fully comprehend exactly how it works due in large part to modern man’s severed connection to the supra-sensory realms. In fact, the effects of this quantum shift have gone largely unnoticed by us. That does not mean, of course, that we do not experience them.

One potential ramification of the phenomenon that Guenon cites is the faster passing of life: “human life itself is moreover well known to be considered as growing shorter from one age to another,” he writes, “which amounts to saying that life passes by with ever-increasing rapidity from the beginning to the end of a cycle.” In this sense, it is not that we are living for fewer years, but that the years themselves are exhausting themselves faster. This is also reflected in noticeable behaviors that are usually blamed on more material or sociological factors. Guenon states:

It is sometimes said, doubtless without any understanding of the real reason, that today men live faster than in the past, and this is literally true; the haste with which the moderns characteristically approach everything they do being ultimately only a consequence of the confused impressions they experience.

This is far from the only observable social phenomenon, however, with the most notable being what Guenon calls “the reign of quantity.” It can be described as an almost obsessive preoccupation with boiling all things down to their “quantity” to the detriment of their “quality,” not only in the realm of material goods (standardization and lowering of artisanal quality), but in the way we view the world around us. This is very pronounced in the realm of science (and, by extension, “Scientism”), which is by nature quantitative due to the ever-present necessity of scientific measurement, but is, of course, not limited to that field, as Guenon explains:

This tendency is most marked in the ‘scientific’ conceptions of recent centuries; but it is almost as conspicuous in other domains, notably in that of social organization — so much so that, with one reservation the nature and necessity of which will appear hereafter, our period could almost be defined as being essentially and primarily the ‘reign of quantity’. This characteristic is chosen in preference to any other, not solely nor even principally because it is one of the most evident and least contestable, but above all because of its truly fundamental nature, for reduction to the quantitative is strictly in conformity with the conditions of the cyclic phase at which humanity has now arrived…

What I found particularly interesting about this description is how much it overlaps with what Jacques Ellul had written about in his book “The Technological Society.” The similarity is effectively summarized in a brief passage which reads: “it might be said that technique is the translation into action of man’s concern to master things by means of reason, to account for what is subconscious, make quantitative what is qualitative, make clear and precise the outlines of nature, take hold of chaos and put order into it.” An example of this principle in action is public opinion analysis, regarding which Ellul states:

This system brings into the statistical realm measures of things hitherto unmeasurable. It effects a separation of what is measurable from what is not. Whatever cannot be expressed numerically is to be eliminated from the ensemble, either because it eludes numeration or because it is quantitatively negligible. We have, therefore, a procedure for the elimination of aberrant opinions which is essential to the understanding of the development of this technique. The elimination does not originate in the technique itself. But the investigators who utilize its results are led to it of necessity. No activity can embrace the whole complexity of reality except as a given method permits. For this reason, this elimination procedure is found whenever the results of opinion probings are employed in political economy.

This is, in my opinion, a great illustration, as it shows quite clearly the limitations of the type of quantitative analysis which our modern civilization gravitates towards, and this same tendency towards uniformity can be observed in countless areas, from psychology, to statistics, to sociology, to economics, to political theory. As we witness the flourishing of the global economy and its deterritorializing and reterritorializing effects (which manifest as the sweeping artificial commodified replacement of all prior paths towards meaning and identity), we can see a tendency towards uniformity overtake our very minds as well.

“Technique, to be used, does not require a ‘civilized’ man,” Ellul states. “Technique, whatever hand uses it, produces its effect more or less totally in proportion to the individual’s more or less total absorption in it.” What this means is that the reign of efficiency, and therefore the domination of quality by quantity, can only result in the eventual “technicization” or “mechanization” of mankind itself. And this is exactly what is happening, as Rene Guenon writes:

The conclusion that emerges clearly from all this is that uniformity, in order that it may be possible, presupposes beings deprived of all qualities and reduced to nothing more than simple numerical ‘units’; also that no such uniformity is ever in fact realizable, while the result of all the efforts made to realize it, notably in the human domain, can only be to rob beings more or less completely of their proper qualities, thus turning them into something as nearly as possible like mere machines; and machines, the typical product of the modern world, are the very things that represent, in the highest degree attained up till now, the predominance of quantity over quality.

There is a sort of irony in all of this, specifically the idea that, as man retreats from what Guenon calls “the principle unity,” that great spiritual center from which all existence emanates, he “unifies” himself in a very mechanical, artificial way. It is almost a mockery of the kind of unity that more spiritual men of the past desperately sought, one which occupies a decidedly lower stratum of existence. Guenon calls this seemingly paradoxical, but ultimately logical, phenomenon “uniformity against unity.” He continues:

The consequence, paradoxical only in appearance, is that to the extent that more uniformity is imposed on it, the world is by so much the less ‘unified’ in the real sense of the word. This is really quite natural, since the direction in which it is dragged is, as explained already, that in which ‘separativity’ becomes more and more accentuated; and here the character of ‘parody’, so often met with in everything that is specifically modern, makes its appearance.

It must be emphasized that numbers, despite being “uniform,” are not “unified,” rather they are separate by nature. Modern man, as a component of his complete desacralization, is molded from birth by the numerical in the form of finances, science, psychological evaluation, algorithms, governmental policy, demographic profiling, etc… thus we are stricken with a profound atomization, despite being surrounded by other humans and despite all of the technology which was intended to link us together. Always together, yet forever alone.

This is further exacerbated by the prevalence of philosophies like Rationalism, which is individualistic in that it denies “everything that is of a supra-individual order” and tasks its adherents with formulating a “rational” worldview through their own power. As Gueonon states: “rationalism and individualism are thus so closely linked together that they are usually confused.” It promotes a fallacious view of human homogeneity by presuming that the “reason” of all human beings works identically while also reinforcing the idea that the onus for moral understanding rests solely on the reason of the individual. This creates the misunderstanding held by so-called “rational” thinkers that people from radically different times and places mentally operate in the same manner they do. Guenon elaborates as follows:

Human nature is of course present in its entirety in every individual, but it is manifested there in very diverse ways, according to the inherent qualities belonging to each individual; in each the inherent qualities are united with the specific nature so as to constitute the integrality of their essence; to think otherwise would be to think that human individuals are all alike and scarcely differ among themselves otherwise than solo numero.

The inevitable consequence of the “reign of quantity” discussed in this chapter is the complete shackling of the man to the realm of the sensory and material, severing him from the subtle influences of higher states of being. “… never have either the world or man been so shrunken,” writes Guenon, “to the point of their being reduced to mere corporeal entities, deprived, by hypothesis, of the smallest possibility of communication with any other order of reality!” The universe as we know it becomes smaller and smaller, while time accelerates until reality is unrecognizable; the unfathomably expansive world system of Mt. Sumeru shrinks to the size of a phone screen.

This in itself is a dreadful thought. Indeed, modern man’s distance from men of the remote past is already extremely wide if we limit ourselves to the current conventional modes of analysis like psychology and materialism, a fact that has led to us so quickly labeling the men of prior ages “naive,” “childish,” and “superstitious” for their vastly different worldviews. If we accept the idea that our very perceptive abilities have been limited by the constraints of the modern condition, the gulf widens to an absolutely staggering degree.

Thus we arrive at the disturbing and very real possibility that subtle forces we can’t sense or comprehend are influencing us in undetectable ways, whether these forces are benevolent or, more likely, malevolent; of a lower plane of existence than even our material one. “It can be said with truth that certain aspects of reality conceal themselves from anyone who looks upon reality from a profane and materialistic point of view,” Guenon writes. “They become inaccessible to his observation.” He continues:

... this is not a more or less ‘picturesque’ manner of speaking, as some people might be tempted to think, but is the simple and direct statement of a fact, just as it is a fact that animals flee spontaneously and instinctively from the presence of anyone who evinces a hostile attitude toward them. That is why there are some things that can never be grasped by men of learning who are materialists or positivists, and this naturally further confirms their belief in the validity of their conceptions by seeming to afford a sort of negative proof of them, whereas it is really neither more nor less than a direct effect of the conceptions themselves.

Thus modern man makes the fatal mistake of believing that the infernal shadow of malefic subtle influence does not exist as long as he does not observe it. “It’s not there when I don’t look.” Yet these are the exact conditions necessary for such a force to overtake the material world, plunging it into a darkness that we can’t even begin to comprehend.

However, there is another aspect to this that must be addressed, that being the aforementioned final “correction” proposed by Guenon in his exposition of the cosmic macrocycle. In service of this, Guenon offers monetary policy as a helpful analogy. Stripped of any higher quality which may have limited the abuse of currency, or as Guenon says “the guarantee of a superior order,” what we see is its continual devaluation:

… it has seen its own actual quantitative value, or what is called in the jargon of the economists its ‘purchasing power’, becoming ceaselessly less and less, so that it can be imagined that, when it arrives at a limit that is getting ever nearer, it will have lost every justification for its existence, even all merely ‘practical’ or ‘material’ justification, and that it will disappear of itself, so to speak, from human existence…

… the real goal of the tendency that is dragging men and things toward pure quantity can only be the final dissolution of the present world.

What’s notable about this is that, like most traditional models of time, it presents a view that is fundamentally the opposite of the progressive narrative that has held Western civilization under its heel for so long. Indeed, such opposition is a key factor in Guenon’s understanding of Traditionalism. As for the aforementioned “dissolution,” however, exactly how it may play itself out will be explored in a later chapter, but I should make it clear here that I do not share the pessimism of Rene Guenon regarding this issue, even if our views do overlap to a certain extent.

In fact, as a Buddhist, I am basically obligated to diverge from his belief in a closely looming end stage of humanity, as the Buddhist understanding of time and cycles (although it indeed shares some features with the Guenonian model) differs to a significant degree. In the next couple of essays, I will outline the relevant differences using both a historical and eschatological analysis of Buddhist scripture.

Chapter 15: The Age of Conflict

“For some time now I have known that this nation is destined for destruction.”

-Nichiren

Returning to the topic at the very beginning of this series: Why exactly did General Ishiwara Kanji, well before the onset of World War 2, believe that Japan was destined for a devastating “final war” with the West?