INTRODUCTION

While the previous chapter explored Nichiren Buddhism and its differences with other Buddhist sects and religions, this chapter focuses in on some aspects of Nichiren’s theories and draws a logical line from them to the politically-charged nature of the Nichirenist movement.

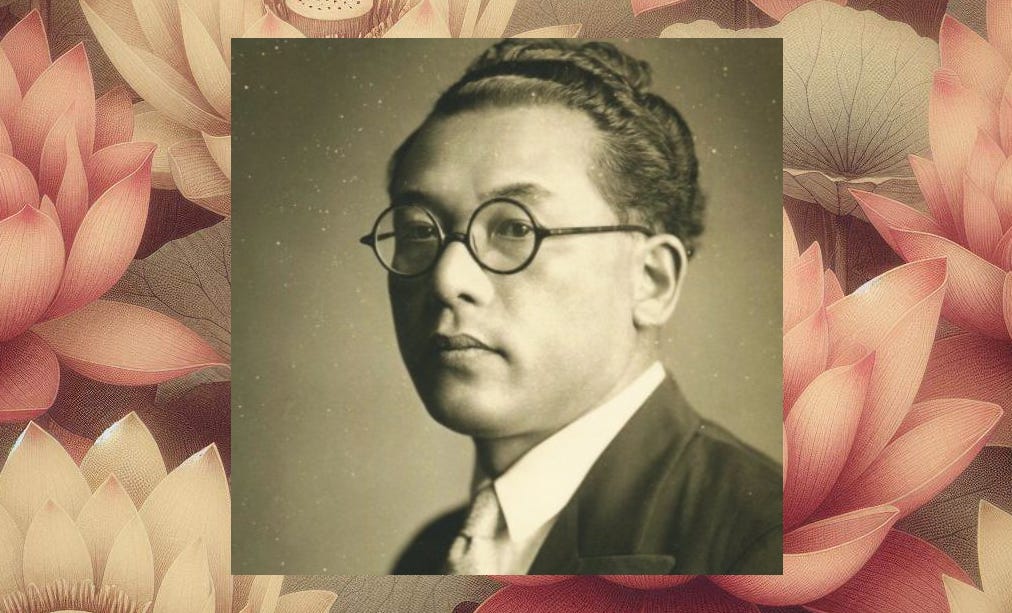

As with the previous entries, my interjections will be in italics. There were only a few instances here, but one in particular I felt required some lengthy clarification, as Professor Kishio Satomi brushes over a certain topic that could have probably been explored in a bit more depth in order to avoid potential confusion (you’ll know what I’m talking about when you see it).

With that said, please enjoy.

JAPANESE CIVILIZATION

ITS SIGNIFICANCE AND REALIZATION

NICHIRENISM AND THE JAPANESE NATIONAL PRINCIPLES

III: THE THREE GREAT SECRET LAWS

(Sandai Hiho)

1. MEANING

After mentioning his Five Critical Principles we must observe what the religion of Nichiren is. He must now establish his own religion as the natural result of his investigations. The Five Principles naturally guide his positive religion, “The Three Great Secret Laws.”

The Three Great Secret Laws are the three aspects of his religion, and they emanated from the One Law which is indicated by the Sacred Title of the Hokekyo. Each of the Three is the independent principle on the one hand, and again each of them is the essential moment of the One Law on the other hand, that is to say something like Hegel's “aufgehobenes Moment.”

It is the three aspects of reality in the sense of the observance of Law; it is the three expressions of the principle of typical personality in the significance of Buddha; it is the three principles of the modes of our lives in the significance of being. Let us reduce the three aspects, then it will be the One Law, and vice versa. From another point of view, the Sacred Title is the religious subject which indicates the Self-containing He. The Supreme Being of the three is the religious object in which the religious subject exists, in other words, it is the He which contains our Selves therein. The Holy See of the three is the concrete realization of the religion.

The Sacred Title is the law of awakening of the individual; the Holy See is the principle of idealization of the country, and the Supreme Being is the harmonious manifestation of the world.

2. THE SACRED TITLE (HONMON DAIMOKU)

The Problem of the religious subject

The title of the Hokekyo is “Myohorengekyo.” But we must mention here that this title is neither a mere title of the Book nor a nominal expression. This, indeed, implies all the value of the Scripture and represents the truth of the Lotus. If the Sacred Title is taken as a mere nominal title it is simply book-worship when people utter “Namu-Myohorengekyo,” “Adoration to Myohorengekyo.” We cannot attain the true meaning without comprehending the title, for the Sacred Title is the essence of the Hokekyo. The Hokekyo is, indeed, an interpretation of the Sacred Title. That is why Nichiren refers to this point so often in his writings. He says:

The so-called Namu-Myohorengekyo is not only the essence of the entire Buddhist Scriptures, but is the heart, the substance and the ultimatum of the Hokekyo (Works, p. 726; see ibid., p. 727).

He preferred the essence, the Sacred Title among the three divisions which are the “Essence,” the “Most Important Portion” and the “Whole of the Scripture.” He denied the value of any Scriptures considered only from a literary point of view. Therefore he says: “Although there are characters and letters of the Hokekyo, they are not the medicine for human spiritual illness.”

He rejected the usual methods of thinking, meditation, reading, researching until people realize the essential quality of religion. According to him, the essence of religion does not consist in such rational practice, but is implied in faith. The Sacred Title is, indeed, the very thing to which our faith must attain in order that we may reach the fulness of the truth. It is, of course, the title, but the title is the key to the contents. Therefore he says:

The name (or appellation or title) is intrinsically justified in calling the thing, and the latter feels it is entitled in its turn to respond. This is the signification of the Sacred Title (Works, p. 229).

According to Tendai, the Sacred Title implies five significations contained in his famous doctrine “The Five Profound Significations” as under:

The Title.

The Entity.

The Principle.

The Efficiency.

The Doctrine.

These five, as a matter of course, are implied in the Sacred Title, for we cannot think of any contents without a title, just as nobody can think of Shakespeare without knowing his name. Nichiren, in this respect, took the Sacred Title as Buddha-Seed, in which all virtues are inherent. Therefore it is an absolute necessity for a man seeking the truth of Buddhism to attain it by dint of practice of the Sacred Title. So Nichiren says:

In the fifth five hundredth period of the beginning of the Latter Law, man shall not believe absolutely the view, though it be Buddha's teaching, that a man can attain Buddhahood, even if he be estranged from the Sacred Title of the Hokekyo (Works, pp. 601, 228-9, 727).

Because, all the letters, 69,384 words of the Hokekyo are nothing but the definition of the Sacred Title, just as in the relation between medicine and the description of its virtues.

The Sacred Title is the essence of the Hokekyo as we have stated above; it means at the same time, the essence of life. Buddha's cosmic life is “Myo-horengekyo,” “Wonderful, mysterious, perfect and right truth.” It is equivalent to the “Real Suchness.” Everything of the universe is therein contained. Nichiren says: “… Therefore the manifestation of cosmos is equivalent to the five words of Myohorengekyo” (Works, p. 684).

The Sacred Title is therefore the principle of our lives or essence of our nature, and further this Sacred Title is the name of life which is analysed into ten worlds, and synthetized into One Buddha Centric Existence under the principle of the Mutual Participation. He writes in this respect as follows:

… Therefore, if one can perceive that it is not a mere title of the Book, but our substance, because Buddha named our substance and nature as ‘Myohorengekyo,’ then our own selves are equivalent to the Hokekyo: and we know that we are the Buddhas whose Three aspects of character are united into One; because Buddha manifested our true substance in the Hokekyo (Works, pp. 659-60 ; see ibid., pp., 228, 341-2).

Nichiren thus taught the intuition for the real self by the law of the Sacred Title. As the result of it, he advocated “Namu-Myohorengekyo,” that is adoration or devotion to the Perfect Truth of the Scripture. In this case, the uttering is one of the important practices comprising about five reasons (Satomi, “Nichiren's Religion and its Practices,” Japanese, pp. 131-3):

Self intuition or reflection.

Expression of ecstasy.

Stimulation of continuous impression.

Autohypnotism for inspiration.

Manifestation of one's standard.

Uttering must probably be studied from the point of view of psychology of religion and philosophy of religion. Without doubt, it is static as far as the Sacred Title is concerned, with the mere idea or conception, but when it is uttered by the voice and is heard by the ear, then it will become a dynamic moment of religion. The Sacred Title is the promise between God and man.

Buddha reveals all His things under the name of the Sacred Title, and beings can see Buddha in it; thus Nichiren thought. When our absolute devotion for the Sacred Title is completed, we can enter into Buddha's wisdom, despite our ignorance. In other words, we can accept Buddha's true wisdom by virtue of faith, that is the absolute dependence on Him. Nichiren explained this faith as the joyful loyal submission. He describes it in an ingenious allegory:

Hearken! Religious faith is simply just like the love of a wife for her husband or a husband's devotion to his wife, or I should say a parent's heart for his or her children or the yearning of a child after its mother (Works, p. 736).

Thus, Nichiren understood the Sacred Title; therefore he says:

Cause and effect of Buddha's enlightenment are innate in the five words of Myohorengekyo. If we keep these five characters, Buddha transfers the fruits of that cause and effect to us in a natural way (Works, p. 94).

In consequence thereof we must carefully note that the Sacred Title is a law which permits individuals to vow to exert themselves to attain Buddhahood. In other words, our allotted lives, at any rate, are imperfect lives, in which divine nature and hellish nature reside together. We must cultivate the divine nature throughout our lifetime. “Namu” therefore means a vow of constant effort for the Attainment of Buddhahood. He says:

Wise and ignorant, all people equally shall utter Namu-Myohorengekyo and abstain from any other vow of the kind (Works, p. 196).

And to this Nichiren particularly draws our attention, he says:

There are two different significations of the Sacred Title between the ages of the Right and Copied Laws and the age of the Latter Law. In the age of the Right Law, Vasuvandhu and Nāgārjunā, etc., adored the Sacred Title which they had limited within their own practices. In the age of the Copied Law, Nangaku (or Eshi), Tendai, etc., worshipped and uttered the Sacred Title, but they did it for the sake of their own practices, and did not propagate it widely to other people. Such attitudes are nothing but metaphysical methods. The Sacred Title which is uttered by me, Nichiren, in the Days of the Latter Law, is totally different from their attitudes in the previous ages. It is a ‘Namu-Myohorengekyo’ for the sake of our own practice and at the same time for the sake of the salvation of all beings (Works, pp. 240-1).

According to him, the Sacred Title must be kept by every individual, and this individual must strive for the salvation of his environment. What he chiefly meant was the instruction of individuals by the Law of the Sacred Title.

Let us consider his doctrine on this point from the point of view of philosophy of religion. Nominalism and realism or substantialism are kept in harmony in this doctrine of the Sacred Title. In addition we see therein a possible solution of the problem of knowledge and faith. He held the value of faith in religion in high esteem, therefore he admonished the people to live in faith. So, he wrote to one of his disciples: “The slight knowledge regarding Buddhism of some of my disciples proved their bane” (Works, p. 729).

Further, he says:

Our knowledge brings no profit whatever. If one has sufficient knowledge to distinguish between hot and cold, one should explore wisdom (Works, p. 1609).

However learned a man may be his knowledge is apt to lead him astray unless he grasps the fundamental wisdom which is different from knowledge. We cannot rejoice in religious happiness without faith. Therefore he says: “One may make oneself a learned man or scholar, but it is of no avail if one goes to hell” (Works, p. 1358).

Thus, he recognized the superiority of faith, but he by no means depreciated knowledge. The essential nature of religion must be faith, but reason and the will, after conviction of faith, lead faith on to the right path. He says:

Be diligent in practice and research, if these two became extinct, then Buddhist Law would have perished. So strive for them and cultivate other people. But in all circumstances, these are derived from faith and belief (Works, p. 502).

Nichiren, moreover, intended to solve the problem of the relation between God and man. If the evil is denied, then goodness must be denied as a matter of course. There is no God outside of our lust, nor divine thing except our nature. Because our nature is existence as a whole, as is shown in the doctrine of the Mutual Participation. Therefore if our lust were annihilated divine nature would then also be nonexistent. From such a point of view he did not adopt Stoicism or asceticism, while on the other hand he did not admit secularism or vulgarism. With regard to this, he asserted that we must spiritualize lust and instinct, but not exterminate them.

Lust will turn into divine power if we spiritualize it. Let lust be divine power, let evil be goodness and let the wicked perform divine action; therein Nichiren's thought lies. Once he writes to Shijo Kingo, a warrior, as under:

Even when in the act of sexual intercourse if one devoted oneself to the Sacred Title, lust would be supreme signification and ‘Life and Death is Nirvana’ would be found in it (Works, p. 853).

He writes again to him:

Utter ‘Namu-Myohorengekyo’ even while drinking wine in company with your wife. Don't let the heart suffer, don't indulge in any pleasure. Be happy to utter the Sacred Title when fortune favours you or during the time of misfortune. Is it not the enjoyment of your own faith of the Hokekyo? (Works, p. 711).

Thus did he teach his disciples, with views which totally differ from the Hinayana Buddhists' view of Nirvana. Therefore such an excellent law of the Sacred Title was declared to Honge Jogyo from Buddha Shakamuni in the Hokekyo for the purpose of propaganda in the beginning of the Latter Law. Let us now cite his writings:

Japan and China, India, nay, the whole world wherein every individual, wise or ignorant, one and all must call on the name of the Sacred Title, Namu-Myohorengekyo. In consequence of the lack of propagation, nobody having kept this law during the last 2,225 years since Buddha's Death, I, Nichiren, alone am unceasingly repeating Namu-Myohorengekyo, Namu-Myohorengekyo, etc. Namu-Myohorengekyo shall last for ever beyond the coming ages of 10,000 years, all the broader and greater in proportion to the magnitude of the benevolence of myself, Nichiren.

This is my merit that destined me to open the blind eyes of all beings in Japan (and in the world) by cutting off the way of communication to the Nethermost Hell. This merit is beyond those of Dengyo and Tendai, and it has an advantage over those of Nāgārjunā and Kāśyapa. Religious austerities (or practice) in the Paradise for a hundred years long are inferior to an accumulation of merit for a day in this impure world. Hearken! All the propagation during the last two thousand years of the Right Law and the Copied Law is inferior to that of a twinkling of an eye in the Latter Days, is it not?

All this superiority is not due to me, that is to say to Nichiren's wisdom, but to the changes of the times. Flowers bloom in spring, fruits ripen into maturity in autumn; it is hot in summer and it is cold in winter. Are these not with the changes of the seasons? (Works, pp. 195-6; paragraphs of “An Essay in token of Gratitude” (to Nichiren's previous old master)).

According to the principle of Mutual Participation, all natures are inherent in our mind a priori, in other words, from God-nature to Satan-nature inhere in us. Therefore even the Buddha or God has quite naturally an evil nature or hellish mind; Buddha is Buddha because He cultivated Himself and He enlightened all hellish natures and made them refined. So also can He redeem evil-natured people. If there is no element of Satan or hell or evil or that sort of thing in God or Buddha, He is a mere spiritual cripple.

How can He redeem evil natures? The conception of Sin must not be dramatized by mythology. Sin co-exists with divine nature in man and in God. But the difference between man and God depends on their effect for the enlightenment of natures. Thus, if we awake in our valuable nature and realize that its value continues everlastingly, in other words, from moment to eternity, from man to God, then we can recognize the true significance of lives. The doctrine of the Sacred Title is shown thus briefly.

3. THE SUPREME BEING (HONMON HONZON)

The Problem of the religious object

The Sacred Title was treated as the problem of a religious subject while the Supreme Being is going to be treated as a problem of a religious object. Every religion has its object for worship. In Nichirenism, with regard to this point, what kind of object is given?

First of all, we must know the meaning of the Supreme Being itself. Three meanings were ascribed to the Supreme Being in Nichirenism. Originally, the word Honzon was a compound noun which can be divided into Hon and Son (Zon is an euphonical change). Hon means Origin and Son means augustness or supremacy. The innate supreme substance is the first definition, the second is the radical adoration, and the third is the genuine or natural respect. All these are slightly different expressions of the Supreme Being and its aspects.

There are two kinds of Supreme Beings in general. The one has the abstract principle as its religious object, while the other has a concrete idea of personality or person itself as its object of worship. In this connection, Nichiren has both simultaneously. According to him, Buddha Shakamuni is the only saviour in this world, therefore we must have Him as our object of religious worship. The following quotation demonstrates it:

Worship, in Japan and the world, the Buddha Shakamuni, the revealer of the Honmon of the Hokekyo, as the Supreme Being (Works, p. 195).

On the other hand, he says: “You shall have the Sacred Title of the Hokekyo as the Supreme Being” (Works, p. 348).

Thus, he founded two kinds of the Supreme Being, the object of worship. In other words, these are the Buddha centric Supreme Being and the Law centric one. And these two are united by him in his most important essay which is entitled “Spiritual Introspection of the Supreme Being,” according to which the Buddha could attain Buddhahood by the virtue of His apprehension of the universal truth, without which a Buddha is impossible.

The Buddha made Himself a Buddha by mastering the perfect truth of cosmos and by its actual realization. From that point of view it can be said that a personal Buddha is secondary if He is compared with the truth itself, on account of the truth being the mother of enlightenment and comprehension. But again, even if there exist such a splendid truth, it will be nothing, or a mere abstract conception at most, unless life be well comprehended and embodied. The Buddha Shakamuni is, indeed, the Sole Tathagata of the perfect truth. The enigma of the truth was enlightened and revealed by Him. Without Buddha's preaching the truth could not be revealed. In that sense, the Buddha made it possible for the abstract truth to become an actual one. Therefore, the Buddha and the truth cannot be separated as far as they are connected with this actual universe.

Moreover, there are many conceptions of the Buddha, for instance, the Threefold personality (Skt. Trikāya), viz. the Body of truth (Dharmakaya), the Body of Wisdom (Sambhogakāya) , the Body of phenomenal person (Nirmanakāya) . These three attributes of Buddha's personality must be kept in harmony consistently. Moreover, as far as the contents of the Supreme Being are the universe, or as long as the Supreme Being is for human beings, the relation between the human nature and Buddha Nature must be solved.

The theory of the Tenfold Suchness in the Hokekyo, as we have mentioned already, guides the principle of the Mutual Participation. According to it, all beings have all the natures and tendencies of their various personal characters innately. Real Suchness, the truth of the universe, exists in such a phenomenon. Reality and phenomena are inseparable. But if there is no one who keeps the truth, then the truth or the law is equal to nothing. However high and sublime the Supreme Being may be, if we ourselves do not enter the ideal of it, and do not realize in our own lives its principle and form, it is just an idol and our existence worthless.

Therefore, all the beings, Buddha and man, saint and layman, must be united under the fundamental primeval virtues of the supreme principle of our lives. Animals, plants, human beings and all deities shall be harmonized into a unity. Nichiren treated plants and animals in reference to the problem of Attainment of Buddhahood as well as mankind (Works, “On the Attainment of Buddhahood of plants,” p. 1293). He diagrammatized this union of the world at Sado during his exile there, and systematized the theory of the Supreme Being in the “Spiritual Introspection of the Supreme Being.” Let us cite a paragraph of his writing:

The august appearance and condition of the Supreme Being are thus: the Heavenly Shrine (Stupa) is flying in heaven over this world of the Primeval Master (Shakamuni). The Buddhas Shakamuni and Taho are sitting side by side and also the four Bodhisattvas, Jogyo, etc., are standing by the Buddha Shakamuni as His attendants on either side of the Sacred Title which is visible in the Shrine.

Monju (Skt. Manjusri) and Miroku, etc., as the followers of the four Bodhisattvas, Jogyo, etc., take the humbler seats, whereas the other innumerable Bodhisattvas sit on the ground like unto people looking up at the courtiers gathered round the throne. Moreover, all the Buddhas who came from the ten directions are on the earth in order to indicate the local realms of the local Buddhas. Such a splendid Supreme Being was not realized during Buddha Shakamuni's days prior to the Hokekyo, even in the Hokekyo, it was revealed only during the eight chapters from XV to XXII (Works, p. 95).

For all beings, gods and men, animals and plants, spirits and demons, he gave the right position in the Supreme Being, the Circle or the Mandala. All of them, without exception, are surrounding the Sacred Title of the centre, in other words, all the beings from Buddha to Hell devoted themselves to the highest truth of the Sacred Title. The Sacred Title is nothing but the Buddha Shakamuni's true name, as well as it is our own inherent nature. Realization of true self through the Sacred Title according to the principle of the Mutual Participation is thus taught. Man or Buddha or God in the highest possible sense can be seen here with the true significance of life. Let us cite one more instance:

How marvellous that, now, I, Nichiren, myself, at the termination of 200 years since the Latter Age began, represented the Great Mandala as the flag of the propagation of the Hokekyo, which Mandala could not be manifested even by Great Masters such as Ryūju (Skt. Nāgārjunā), Tenjin (Skt. Vasuvandhu), Tendai and Myoraku.

However this is in no manner, my, Nichiren's, own invention, but it is proved by the Buddha Shakamuni and all the distributive Buddhas in the Heavenly Shrine. The Sacred Title, therefore, is hoisted in the centre and the Four Great Demon Kings (Japanese: Shidai-Ten-no who guard the world against) [They are more commonly known as the “Four Heavenly Kings”] Ashura (Skt. Asura) take seats at the four corners in the Heavenly Shrine, the Buddhas Shakamuni and Taho and the Four Primeval Bodhisattvas (Honge Jogyo, etc.) stand abreast, Fugen (Samanta Bhadra), Monju, Sharihots [the disciple Shariputra], Mokuren [Maudgalyāyana, another disciple], etc., take the humbler seats, the gods of the Sun and Moon, the King of Mara of the sixth Devaloka, the Serpent King and Ashura also join the body, moreover Hudo [Fudo Myo-o] and Aizen are seated in the direction of south and north, atrocious Devadatta, the folly serpent maid [i.e. Dragon King’s daughter], the mother of demons, Ten wives and daughters of the devils (Japanese: Kishimojin, Skt. Rākchasa) who make attempts on human life; then the Sungoddess and God of Hachiman, both of the genius of Japan; the gods of heaven and earth, all kinds of deities, gods-in-nature are present ; how much more gods-in-themselves. In Chapter XI it says:

“As the Lord apprehended in his mind what was going on in the minds of those four classes of the assembly, he instantly by magic power, established the four classes as meteors in the sky, etc.” (Kern, p. 237 ; Yamakawa, p. 355). These Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and great sages and all other beings, Two worlds and Eight kinds (i.e. all kinds) of beings who were present since the Introductory chapter of the Scripture, altogether, without exception, live in this Supreme Being, and all of them realize their innate value of personality under the brilliant light of the Five Characters of Myo-ho-ren-ge-Kyo. Such is the Supreme Being (Works, pp. 721, 722).

Keeping this in view it will be easy to understand that Nichiren's idea consisted in “Coincidencia oppositorum“ and “Synthetic union.” According to him, all beings on the one side are a mass of lust, but nevertheless they are, on the other side, Buddha in nature or Buddha in substance. Therefore if they would self-awaken to their true value and strain every nerve to get near their intrinsic Buddhahood, significant lives would be established.

For that reason he divided the Buddha into two kinds, viz. Buddha-in-Nature and Buddha-in-Realization. The former corresponds to normal man and the latter means Buddha himself. Besides, all beings from the Buddha to Hell or from man to all lower animate creatures are united in the highest principle, that is to say, Myohorengekyo. Thus, this Mandala is, indeed, the real form of the Real Suchness or the world or self or the class harmonization. He, therefore, strongly advocated this Supreme Being in the absolute sense. He writes on the right side of the Supreme Being as under:

This is the Great Mandala which has never before appeared in this world during these two thousand two hundred and twenty years since Buddha's Decease.

On the left side is written:

Having been condemned to die on the twelfth day of the ninth month, in the eighth year of Bunn-nei, but as I had, instead, been exiled later on to the distant Isle of Sado, on the eighth day of the seventh month, in the tenth year of the same, I, Nichiren, make this representation for the first time.

Thus Nichiren made the Supreme Being in a perfectly graphical method, which is much more effective than the ordinal Buddha's image or Buddha's picture or an abstract heaven. In this representation we can see that he treats several forms of worship under the principle of unity as under:

Dendolatry in the lotus, theriolatry in the serpent, demon-worship in the Mother of demons, great-man-worship in Tendai, etc., King-worship in Ajase, Godman-worship in Shakamuni, iconolatry in the Four Great Devas, racial-god-worship in the Sungoddess of Japan, national-god-worship in Hachiman of Japan, and ancestor-worship in ancestors, etc. etc.

Of course, all of them are united together by the principle of Myohorengekyo. We can identify ourselves with Buddha Himself if we truly awake and strictly practise the Attainment of Buddhahood. So Nichiren says:

The Heritage of the Sole Great Thing Concerning Life and Death can be understood in the utterance of the Sacred Title, with the conviction that Buddha Shakamuni, who has attained Buddhahood from eternity, the Hokekyo and all beings, these three are but one (Works, p. 677).

The interpretation of this doctrine has not yet been fully given, but we cannot expect to succeed in a technical explanation in this book, so we shall, for the present, examine a few problems concerning this thought.

There are two tendencies about the conception of God which must be noticed. The one is pantheism and the other is monotheism. Pantheism identifies God in nature, or looks upon Nature as partial appearances of the sole and absolute God. It shows immanency of God in opposition to deism. The Eleatics, Xenophanes, Parmenides, etc., advocated this theory in an early age, and Bruno, Spinoza, Fichte, Schelling, Hegel, Schleiermacher, Hartmann, Wundt, Lotze, etc., conceived this thought also. Spinoza is a pioneer of this thought in the modern age and his famous words “Deus sive natura” (God is nature) are quoted as the motto of pantheism.

Pantheistic thought in the history of religion germinated mainly among Aryan races and, according to Tiele, what is called theanthropic religion. Pantheism, as a rule, has a great system and a great ideal, and gives us not only a sensitive satisfaction, but likewise a rational one. But in pantheism there is no union in its vast system, and so it is very difficult to fix the religious object which is the object of our sentiment. Therefore religious practice can hardly be the outcome of it. If we look upon the universe or nature as a religious object there is, indeed, no religious object. Or if we consider our slight efforts of daily life as divine acts or religious practice, it is equal to having no religious practice at all. To make such pantheistic thought possible a deistic thought or an atheistic colour or maybe a polytheistic idea must be adduced.

On the other hand, monotheism has the One God who created this world from another world. The nature of God in monotheism is quite different from that of polytheistic gods. God is transcendent and we cannot mix up God and the universe. God and the world are totally different things. According to Tiele this is called theocratic religion, and originated among the Semitic races. The representative religion of the former is Buddhism, while Christianity is the highest development of the latter.

It is quite natural that mechanism or causality grew in the former thought and teleologism or finality comes from the latter. The characteristic of the former religion is tolerance and of the latter intolerance. Von Hartmann gave a suggestion concerning the future religion in his “Religionsphilosophie.” According to it, the religion which is worthy of the future has to unite these two different tendencies in harmony. But we cannot find the possibility of the unity in the Bible nor in the ordinal Buddhist Scriptures. In other words, there are no foundations on which to unite them in these Sacred Books.

In the Bible there is the chapter of “St. John” which accepted abundant pantheistic thought, under the influence of Scholastic philosophy, in order to fill up the original weak point of the Bible. But there is no foundation for uniting them in the whole Bible. Hinayana Buddhism is known as atheism in that it denies the Divine One and only aims at Nirvana. On the other hand, there are pantheism and monotheism in Mahayana Buddhism, for instance, the Shingon Sect, the Zen Sect, the Tendai Sect, etc., belong to pantheism, and the Shin Sect or Jodo Sect belongs to monotheism; but they also have no foundations on which to unite these opposite tendencies.

[Editor’s note: Shingon esoteric theological understanding does place Mahavairocana as a central, all-encompassing figure, something which is shown out in their mandalas, meaning there is some semblance of what could be called monotheistic thought within the religious framework of the sect. However, I believe the professor here is describing these faiths in terms of popular practice, i.e. how the form of religious devotion takes shape in daily life. In this regard, Shingon and Tendai can appear similar to pantheistic paganism, lacking in the holistic quality that Professor Satomi believes to be necessary.

Western readers may also be confused about the inclusion of Zen here, as modern Westernized forms of Zen tend to be on the iconoclastic side of things, sometimes bordering on secularization, but Japanese temples still tend to be heavy in the iconography and mysticism that their Western “Zen center” counterparts have largely abandoned. Moreover, Professor Satomi specifies in regards to pantheism: “if we look upon the universe or nature as a religious object there is, indeed, no religious object.” In this sense, I believe that both iterations of Zen could indeed fit under the descriptor.]

Nichirenism is the answer to this problem. First of all, in the Hokekyo, we have the doctrine of “Six Ors " which throws a light on this problem. According to this thought, the Primeval or Fundamental Buddha, whose deep sense of His existence is explained in Chapter XVI in the Scripture, as we have mentioned already, is unique and sole God in the Universe, and all the beings and all the divines or sages and wise men are nothing but His distributive bodies. It says:

… or I explained about my own appearance, or about others'; or appeared myself, or under the mask of others; or showed my own action, or others' (Yamakawa, pp. 459-60 ; cf. Kern, p. 301).

Moreover, it is stated in other lines:

All young converted men! Whenever people came and saw me, I considered and observed their different degrees of faculty of faith and so forth, and I preached the Law under the different names (of Buddhas, gods, sages or wise men, etc.) and the strength of succeeding generations in various places; and again I revealed my lives and proclaimed that I shall be in Nirvana before long; and delivered mysterious laws with various pious impositions and allowed beings to feel ecstasy (Yamakawa, pp. 458-9; Kern, p. 300).

Therefore, Nichiren says: “The Buddha of the ‘Duration of the Life of the Tathagata’ reveals Himself even in the lives of Grasses (Herbs) and Trees” (Works, p. 1293).

It is evident that in these lines Nichiren's One Buddha Centric Pantheism, as Yamakawa expresses it, is firmly established. And then the following view is possible, that Confucius or Christ or Mohammed or any sages are nothing but one of the distributive bodies of this One and Only Buddha. Nichiren recognized the One Buddha as the sole and highest existence, who revealed Himself as Eternal Buddha in Chapter XVI of the Hokekyo, but at the same time he acknowledged the divine nature as intrinsically inherent in all beings, according to the principle of Mutual Participation of the ten worlds. He holds with monotheism in the former sense and holds with pantheism in the latter sense. But as he says in his letter to a lady, Nichinyo (Works, p. 721), he took up the position of One Buddha Centric Pantheism as his ultimate decision. We can see here one of the reasons for determining what the condition of the future religion will be.

Buddhism and Christianity belong to the absolute religion which is acknowledged as the highest development of all religions. Buddhism is called absolute subjective religion and Christianity, absolute objective religion. But it is not so easy to thoroughly unite subjectivism and objectivism in one religion. Religions, in all probability, are one-sided on this point.

As I have mentioned before, deistic thought or objective absolutism is prone to modify its main portion to subjective absolutism in order to bring itself into firm existence. For instance, Christianity adopted Greek philosophy, which implies much theanthropic thought, in the effort to remedy its original defect. But, at the same time, the subjective absolutism is liable to fall into atheism after running to excess.

The motto in the Zen Sect that states “This mind is Buddha,” shows an extreme absolutism, which however causes self-overestimation and denies the pure religious sentiment of absolute dependence on God. Let us take one more example, the Nenbuts Sect (Jodo and Shin Sects) is a typical objective absolutism like Christianity, therefore there is a consistent unity with regard to the religious object and consequently it has a strong religious force, nevertheless there is no possibility of uniting the subjectivism in its system.

But it seems that a possible solution of this point is given in Nichiren's doctrine of the Supreme Being: “There are three in Father: that is, the Myohorengekyo, the Buddha Shakamuni and Nichiren, myself.” This is a paragraph of his “Ongikuden,” which is a report of his lectures on the Hokekyo in his later days in Minobu, and we find in it a similar conception to the theory of the Christian Trinity. The conception of Myohorengekyo is the absolute object of our religious faith, but, at the same time, if a man be enlightened and can identify the principle of personality with that of the absolute law in the same breath, then this subject could be harmonized with the object.

In other words, it does not mean that we, as we are, are not Buddha Himself, but if we cultivate our Buddha nature and adore the Sacred Title with the most sincere attitude, we can then realize the true innate value of ourselves. Therefore, Nichiren's instruction is given below :

If you are at One in Faith with me, Nichiren, you are one of the saints-out-of-the-Earth; and such being your fate, how can you doubt your being the disciple of the Buddha Shakamuni from the earliest ages onward? Buddha declares: From eternity have I been instructing all these beings (Yamakawa, p. 445 ; Kern, p. 293).

No distinction should be made between men and women among those who would propagate the Perfect Truth of the Hokekyo in the days of the Latter Law. To utter the Sacred Title is the privilege of the saints-out-of-the-Earth " (Works, p. 686).

Thus, the religious subject and object can be one and the same by intermediation of “Adoration to the Perfect Truth of the Hokekyo” according to the principle of the Mutual Participation. This thought is worthy of suggestion for the problem of unity of religious subject and object.

Moreover, we can see in this doctrine the relation between the ideal world and the actual one. It is absolutely useless to seek the ideal world under the name of paradise after completing this life. Of course, we believe in an after-life as well as a past life in a religious sense. But we cannot demonstrate the past nor the after-life, therefore the after-life is possible only as a religious postulation. In short, we must apprehend the meaning of past and future in the very present, hence the present centric consistentism through the three lives, viz. the past, present and future. In respect thereof we shall have a full explanation and idea of Nichiren by our understanding of the doctrine of the Holy See.

Now, let us not neglect another important thought on the Supreme Being. Nichiren wrote down in the Centre of the Supreme Being as follows:

This, no doubt, indicates a most important thought of Nichiren; it was suggested to him by the doctrine of the Ten Mysterious Laws of the Honmon in the Hokekyo. The so-called Three Radical Mysterious Laws among the ten are applied in the centre of the Supreme Being.

The Three Radical Mysterious Laws are as under:

Mysterious Law of Original Effect.

Mysterious Law of Original Cause.

Mysterious Law of Original Land.

All of them, originally, were the doctrine concerning the Primeval Buddha. Let us interpret this as far as may be necessary. The Primeval Buddha who had attained Buddhahood from all eternity, in other words, the Buddha who revealed Himself as the eternal saviour in Chapter XVI of the Hokekyo, reveals Himself in at least the three aspects. First of all, He reveals Himself as the Perfect Buddha who is the highest effect of cultivation. That is the Mysterious Law of Original Effect. It runs in the Hokekyo as under:

Listen then, young men of good family. The force of a strong resolve which I assumed is such, young men of good family, that this world, including gods, men, and demons, acknowledges: Now has the Lord Shakamuni, after going out from the home of the Shakas, arrived at supreme, perfect enlightenment, on the summit of the terrace of enlightenment at the town of Gaya. But, young men of good family, the truth is that many hundred thousand myriads of Kotis of Æons ago I have arrived at supreme, perfect enlightenment. By way of example, young men of good family, let there be the atoms of earth of fifty hundred thousand myriads of Kotis of worlds; let there exist some man who takes one of those atoms of dust and then goes in an eastern direction fifty hundred thousand myriads of Kotis of worlds further on, there to deposit that atom of dust; let in this manner the man carry away from those worlds the whole mass of earth, and in the same manner, and by the same act as supposed, deposit all those atoms in an eastern direction. Now, would you think, young men of good family, that any one should be able to imagine, weigh, count, or determine (the number of) those worlds?...

I announce to you, young men of good family, I declare to you: However numerous be those worlds where that man deposits those atoms of dust and where he does not, there are not, young men of good family, in those hundred thousands of myriads of Kotis of worlds so many dust atoms as there are hundred thousands of myriads of Kotis of Mons since I have arrived at supreme, perfect enlightenment. From the moment, young men of good family, when I began preaching the law to creatures in this Saha-world and in hundred thousands of myriads of Kotis of other worlds (Kern, pp. 298-300; Yamakawa, pp. 455-8).

Secondly, even the Buddha cannot be Buddha without having any cause to be Buddha. Therefore He says:

Once I had practised the Bodhisattva-course and accomplished the life which is still everlasting, nay, it is multiplied by the above numbers (i.e. 500,000 myriads of Kotis). (Yamakawa, p. 461; cp. Kern, p. 303).

The mysterious Law of Original Cause is shown as above. But if such things only are done in heaven then there are nothing but matters-in-heaven. Buddha's contention, however, is quite different from such an imaginary tale; he, obviously, mentioned such a practice on the earth. Consequently the next problem is the one concerning the background wherein such mysterious things have been actually done. Buddha says: “From the moment when I began preaching the law to creatures in this Saha-world.” Or further:

And when creatures behold this world and imagine that it is burning, even then my Buddhafield is teeming with gods and men. They dispose of manifold amusements, Kotis of pleasure gardens, palaces, and aerial cars; (this field) is embellished by hills of gems and by trees abounding with blossoms and fruits. And aloft gods are striking musical instruments and pouring a rain of Mandaras with which they are covering me and the disciples and other sages who are striving after enlightenment. So is my field here, everlastingly; but others fancy that it is burning; in their view this world is most terrific, wretched, replete with numbers of woes (Kern, p. 308; Yamakawa, p. 471).

This is the Mysterious Law of Land.

If there be such individuals who practise the Buddha's Way and there are Buddhas, then the country or the world which consists of the above beings must be the ideal world. The Sole Buddha, according to the Hokekyo, reveals Himself in these three aspects, but the three are one. Nichiren founded the system which I mentioned above, from this point of view. “Namu-Myohorengekyo,” “Adoration to the Perfect Truth of the Lotus,” means the first “Mysterious Law of Original Effect,“ “Sungoddess and Hachiman” is the “Mysterious Law of the Original Land” and “Nichiren” means the “Mysterious Law of Original Cause.”

Of course, Myohorengekyo is the content of the Buddha Shakamuni's personality, that is to say, it is another name of the Buddha. Therefore, it is quite natural to mention it as the Mysterious Law of Original Effect, namely He manifested the highest effect of attainment of our personality through sincere cultivation.

Nichiren is, of course, in this case, the prophesied person as the executor or performer of the Hokekyo in the age of the Latter Law. There is no doubt that he performed all his duties precisely according to the indication and prophecy of the Hokekyo: that is, he exemplified how to live in order to attain Buddhahood.

But the Sungoddess is the Imperial ancestor of Japan, and the God of Hachiman is also a Japanese national God. Herein some people might imagine a narrow-minded notion of nationality, whereas it is, in fact, the most important problem in Nichirenism as the universal religion, and will be fully discussed in Chapter V ( Works, pp. 722, 94, 707, 240, 661-6, etc.).

4. THE HOLY ALTAR (HONMON KAIDAN)

The Problem of the Synthetic Creation

The third important thought in Nichirenism is the Holy Altar (or the Holy See). Nichiren founded his most concrete idea of his religious practice on this doctrine. As I have stated above, the Sacred Title was mentioned for the instruction of individuals, the Supreme Being was for the world or universe, and, from this point of view, this Holy Altar is the key to the enlightenment of the country.

Moreover, this Holy Altar, in a sense, is the connection between the Sacred Title and the Supreme Being; namely the Holy Altar shows the concrete method of entering the Supreme Being, and how to adore the Sacred Title, the essential law of Buddhism. As we shall see later on, the doctrine of the Sacred Title appeared in the early days of Nichiren's activity, and that of the Supreme Being was developed in Sado during his last exile, by which the prophecy of the Hokekyo about him was fully realized. The doctrine of the Holy Altar was proclaimed in the days of his retirement in the recesses of Minobu, and is, in fact, the very centre of his religious movement, and upon it his vast system of religion mainly depends. We must therefore examine this thought comparatively and circumstantially.

Let us bear in mind the general idea of the Buddhist Holy Altar prior to Nichiren's statement. The Commandment or precept in Buddhism was valued by all Buddhists, and it was put forward as the sole practical method to attain Buddhahood. Two definitions are given concerning the commandment in Buddhism. The one is “To prevent misdeeds and wickedness” and the other is “To prevent wickedness and do good.” In this sense, Hinayana Buddhists have the Five or the Eight or the Ten, or the Two Hundred and Fifty, or the Five Hundred commandments, according to their different conditions; and Mahayana Buddhists also have the Tenfold or the Forty-eight commandments. There are besides, special commandments in the Hokekyo, the one is the Shakumon Centric Commandment and the other is the Honmon Centric one. Laymen, monks, nuns and all sorts of human beings are entreated to keep these commandments.

However, all these commandments can be comprised in two parts according to their essential meanings. Formal commandment is the one and Idealistic commandment is the other. For instance, all Hinayanistic Commandments and those of the general Mahayanism belong to the formal commandments, while the commandment of the Hokekyo belongs to the idealistic one. From the point of view of the former, all the rules must be kept by people formally, while the deep idea of commandment is associated with the latter. We can say nothing about the history of the development of the commandments here, nevertheless, it is evident that the vicissitudes of the Buddhist commandment can fairly be compared with the rise and fall of the doctrine which I have previously stated.

The Great Master Dengyo, with reference to this, adopted the Shakumon centric idealistic commandment, while he rejected the Hinayanistic ones and those of the general Mahayanism. Dengyo, however, held, with the Shakumon centric commandment, the former fourteen chapters of the Hokekyo; therefore, he could not go further with the Honmon. Consequently, he adopted the Tenfold Prohibitive Commandments of the Bonmokyo (Skt. Brahma Djāla Sūtra) [Brahma’s Net Sutra], holding at the same time with the Shakumon centric idealistic commandment.

Nichiren, on the contrary, adopted only the Honmon centric one and strictly prohibited any other kinds; because he saw the reason from the fact and the proof of the Scriptures that there is no authority maintained concerning the formal commandment in the days of the Latter Law. It would be too ineffectual to stipulate that a man should be such and such only by formal rules in this world of five turbidities or impurities. We must attach more essential significance to commandment by refraining from such external rules; in other words, it is much more important to give signification of life in the depths of people's minds than to give the ordinal arrangement of actions and appearances.

Of course, there is no doubt that these old-fashioned commandments were very effective at one time in early ages, but are too formal and too powerless to adapt to the age of the Latter Law. The age and people must have more internal authority, namely the commandment must be such as to give fundamental rules in the internal personality, with the most simple and authoritative dignity. Nichiren, therefore, rejected the Hinayanistic and general Mahayanistic commandments in consideration of their powerlessness, and, it may be added, with the authority of many Buddhist Scriptures on this point. He says:

Now, the commandments are the Hinayanistic Two Hundred and Fifty rules. With reference to the first commandment, namely ‘Thou shalt kill no living being,’ in all the Scriptures except the Hokekyo, it is said that the Buddha kept this law. But the Buddha, who is revealed in these Scriptures with pious imposition, starts by killing, so to speak, from the point of view of the Hokekyo. Why? Because, although it seemed that the Buddha in these Scriptures kept the law in His daily affairs, yet He did not keep the True Commandment of ‘Kill no living being’: because He killed the possibility of Attainment of Buddhahood of all other beings except Buddhas Themselves, so that the beings were not allowed to attain Buddhahood. Thus, the leader, the Buddha, is not yet released from the sin of Killing, how much less the disciples (Works, pp. 365-6).

Therefore, Nichiren gives significance to one's free will, which means in a sense an imperative category. This is a different point from that of the ordinal commandment which governs several of our acts superficially. He united the teachings and commandments which are explained together in the Nehangyo, from the point of view of the doctrine of the Hokekyo.

Although a man makes himself a perfect Buddhist, if it is limited to a mere individual personality and has no positive effect in protecting and spreading the Buddhist Law, then all exertions are in vain. However much one may be faithful to the mere individual formal commandment, it is of no use unless one awakes to the signification of one's existence. Thus Nichiren thought. According to him, the signification of one's existence can be filled up with ardent vows for the protection and enlargement of the Law.

Nichiren saw the Mysterious Law of the Hokekyo in the very mysterious power whereby people do righteousness and goodness, even though they be bad and evil. If the Attainment of Buddhahood were only granted to those possessing a perfect personality from every point of view, then the Attainment of Buddhahood would be an imagination. Even a man with defects in his character, if he awakes to the signification of life, that is to the protection and enlargement of the perfect Law, and if he acts according to this ideal, then his act is equivalent to that of the Buddha-course, notwithstanding that his defects are not yet eliminated. Of course, according to Nichiren's view, the moral cultivation of individuals is doubtless important, but belongs rather to common sense, and is therefore treated in the doctrine of the “Four Instructive Methods” (Shi-shits-dan). One of the paragraphs in the Hokekyo which was very often cited by Nichiren as the demonstration of this thought is to the following effect:

Not only I myself shall be pleased, but the Lords of the world in general, if one would keep for a moment this Sutra so difficult to keep. Such a one shall ever be praised by all the Lords of the world. Such is courageousness, such is assiduous advance (Skt. Vīrya; Japanese, Shōjin). I call such a man the true practitioner of Buddhism (Skt. Dhūta; Japanese, Zuda) and the true keeper of the commandment (Yamakawa, pp. 363-4; Kern, p. 242. This translation is partly Kern's and partly mine.)

To transfer the ideal of the Hokekyo to man's daily life is equivalent to keeping the commandment. This is the commandment of the Hokekyo. In other words, the namu or to devote oneself to the propagation of the Law of the Scripture is equivalent to “Keeping the Commandment.”

From this point of view Nichiren saw two aspects of the commandment of the Hokekyo, that is self-devotion to the essential law of the Hokekyo and its realization and extension to the whole world. In order to spread this law over the world, some attacks must be made on all kinds of evil; nay, it is absolutely necessary to eradicate the evil. This was suggested to him by the Nehangyo (Skt. Mahāparinirvāna-sūtra or the Scripture of Buddha's Great Decease) and the Hokekyo. On the one hand, he proclaimed that “To keep the Sacred Title is the commandment.” He says:

The five characters of Myohorengekyo, the essence of the Honmon of the Hokekyo, are stated as the assemblage of all virtues of all the Buddhas in the past, in the present, and even in the future. Why should not the five characters contain all virtues and effects of all the commandments (Works, p. 324).

We must also not neglect the following results which are cited by Nichiren (from the Nehangyo) very often as being one of his thoughts about the commandment. It says:

However virtuous a priest may be, if he neglects to eject transgressors, to make them repent or renounce their sins, hearken! He is wicked and hostile to Buddhist Law. If he casts them out to make them be repentant and amend their negligence, he is worthy to be my disciple and truly virtuous.

Thus the idea of the Hokekyo does not admit of a mere self-complacency in faith, but it demands absolute reconstruction and instructing one's environments. Therefore, the definition of faith is much different from the ordinal ones in other religions. The significant purport of a Nichirenian's faith must be a combination of both, which is self-devotion and social reconstruction, therefore he says:

How grievous it is that we were born in such a country wherein the right law is disparaged and we suffer great torment! How shall we deal with the unbelief in our homes and in our country, even though some people observe the faith of the Law whereby they are relieved of the sin of individual disparagement. If you desire to relieve your home of unbelief, tell the truth of the Scripture to your parents, brothers and sisters. What would happen would be detestation or belief. If you desire the State to be the righteous one you must remonstrate with the King or the government on its disparagement of the righteous law, at the risk of capital punishment or banishment.

... From all eternity, all failures of people to attain Buddhahood were rooted in silence about this, out of fear of such things (Works, p. 651).

The conception of the commandment, therefore, is not merely negative virtue of individuals, but undoubtedly a strong vow for the realization of a universal or humanistic ideal paradise in this world.

According to Nichiren, the heavenly paradise has not an allegorical existence, but is the highest aim of living beings in the living world, in other words, it must be actually built on the earth. For such a fundamental humanistic aim we must all strive. The true commandment has not its being apart from the vow. If one fully comprehends his thought, and will strive for it, then the signification of one's life will be realized. This thought is the most important idea of Nichiren's religion, and, in fact, the peculiarity of Nichirenism consists therein. For him, to protect and extend the righteousness over the world, through the country and to everybody is the true task of life. Consequently, he tested what would be the most convenient way of realizing such an ideal in the world, and he found the country for it.

The country or the state, of course, is the secondary production of human life because of the order of its origination, but as a matter of fact, with regard to our present civilized world, individual beings are preceded by the country. With regard to the method of salvation, the country must be classed as the unit. All existing methods therein are in all probability mere individual standards; on the contrary it is the country or the state standard as regards Nichirenism.

Of course, as we have already mentioned, the country or the state is without doubt the highest civilization, and the world is divided into various countries, and all the individuals, too, are divided into several nations. Consequently, the world in accordance with observation, from a point of view of the methodical system, cannot exist apart from the countries. The individual cannot live without the country, or I should say the individual who does not belong to any country, if such there be, could not demand or be entitled to civilization.

In the religious sense, the unification of the world or the salvation of the world is impossible unless the religion and the country assimilate. Nichiren, therefore, determined the country as the unit of salvation of the world as far as method is concerned. He says:

Hearken! The country will prosper with the moral law, and the law is precious when practised by man. If the country be ruined and human beings collapse, who would worship the Buddha, who would believe the law? First of all, therefore, pray for the security of the country and afterwards establish the Buddhist Law (Works, p. 13).

This is a paragraph in his important essay, “Rissho Ankoku- ron” or “An Essay on the Establishment of Righteousness and Security of the Country.” He discoursed on the relation between the country and religion in this essay and sent it to the Hojos Government at an early date as an intimation of his religious movement; but this thought fully developed by degrees and eventually the doctrine of the Holy Altar was founded. There is no doubt that Nichiren thus thought of the country as the most concrete basis on which to propagate religion.

The intention of realizing a religious paradise by the purification of each individual might be compared with a person vainly calculating to disprove the decimal system. It would be like fresh and savoury meat being placed on an unclean dish, thereby destroying the flavour of the good meat. However righteous each individual might be, if his environment, which is the country, be greedy, his Attainment of Buddhahood would be, to put it briefly, incomplete.

Therefore, as remarked by me in the introduction, the standard of the religious cultivation must be determined by the congregational body, the representative of which is the country. The country contains various things, viz. the subject and object of sovereignty, diverse societies, education, law, military force and economical power, etc. etc. These things have a concrete influence on the nation, not even a single one of them can be neglected. Consequently, the religion of the future shall have all these things as objects of salvation. Religion is intended to redeem living beings and their environment. Therefore, religion must purify the whole concrete life of man in order to religionize all individuals and the world.

If religion does not in any sense concern material life, but merely spiritual life, then is religious influence almost in vain. A belief which purposely eliminates material affairs from the religious field is not only a misunderstanding of the essential meaning of religion, but is a very wrong view of human life. The true religious Empire can be established in the material world which is purified with spiritual signification. Nichiren's doctrine of the Holy Altar is, indeed, an enlightenment of religion with material purification. To unite the spiritual force and the material may have been discussed in the past, but it still remains unsolved. The lopsidedness of spiritualism in the field of religion has caused the present weakness and inefficiency of all religion in spite of preachings. Enlightenment and guidance to the material life is an absolute necessity if man does not live spiritually only.

The country, in this sense, is the representative material organization, so to speak. In fact, human life is saved, is protected, and is watched over by the country. The individuals form the country and society, despite individuals being forced to control their concrete lives. Of course the individual has the supernational will, but he is forced to obey the national laws. It is evident that international society is now becoming of much greater significance than the country in human life; international society is wider and higher than the country, or at least the racial combination is stronger than society.

Of course, according to modern interpretation, Nichiren's thought of the country naturally implies two aspects which are the country and society. At any rate, for him, such a combined body of human lives was thought most important for the religious salvation of the world. The country is not the ultimate aim of the human ideal, it must be the universal ideal society, consequently, the country must be such as to have ultimately a purposive unity in joint existence or co-operative aim. While the existing countries have no fixed idea on this point, correspondingly so many countries are the greedy enemies of one another. Therefore, to realize the ultimate human ideal world we must, to begin with, reconstruct the country so that it may exist hand in hand with righteousness.

According to Nichiren, in the degenerate days of the Latter Law, there is no Buddhist commandment outside of our vow for the reconstruction of the country and the realization of the Heavenly Paradise in the world. Even the so-called virtuous sage, if he does not embrace this great and strong vow, in other words only enjoys virtue individually, such a sage is pretty useless.

Although a man be imperfect, let him carry out Buddha's task with the strong vow for the realization of Buddha's Kingdom, with preaching or with economical power or with knowledge of sciences and with all sorts of such things. We can find the true significance of religion, of commandment, of human life therein.

The protection of moral law is the sole task of human life, and this is the greatest invention and discovery of our lives. When one digresses from and acts against the moral principle, one is no longer worthy of being a human being, thus Nichiren thought. Consequently, weapons, army, education, commerce or the life, everything must be for the sake of true human life, which means the practice and the protection of moral laws. Buddha says in the Nehangyo:

In spite of a man accepting and keeping the Five Commandments, he cannot be called a man of the true Mahayana Buddhism. One who protects the right law is the man of the true Mahayana Buddhism, even though he does not keep the Five Commandments. The man who protects the right law shall be armed. Him do I call the true practitioner of the Buddhist Commandments though he is armed.

This thought is also apparent in the Hokekyo. It says in Chapter XIV:

It is a case, Mangusri (Japanese, Monju or Mon-jushiri), similar to that of a King (Tenrinjo-o; Skt. Chakravarti-raja), a ruler of armies, who by force has conquered his own Kingdom, whereupon other Kings, his adversaries, wage war against him. That ruler of armies has soldiers of various descriptions to fight with various enemies. As the King sees those soldiers fighting, he is delighted with their gallantry, enraptured, and in his delight and rapture he makes to his soldiers several donations, such as villages and village ground, towns and grounds of a town; garments and head-gear; hand-ornaments, necklaces, gold threads, ear-rings, strings of pearls, bullion, gold, gems, pearls, lapis lazuli, conch-shells, stones (?), corals; he, moreover, gives elephants, horses, cars, foot soldiers, male and female slaves, vehicles and litters (Kern, p. 274; Yamakawa, p. 415).

Therefore, Nichiren proclaims:

Know ye, that when these Bodhisattvas act in accordance with the positive instruction, they will appear as wise kings and attack foolish kings in order to instruct them; when they will act negatively then will they appear as priests and propagate and keep the right law (Works, p. 103).

In that relation did Nichiren acknowledge military force, he accordingly wrote an instruction to one of his great supporters, Shijo Kingo, who was a typical Japanese warrior: “Prefer the art of war to any other art, even any branch connected therewith shall be rooted in the Law of the Hokekyo” ( Works, p. 907).

Of course in this connection it is not his intention to interfere with anything relating to the substance itself, but it is mentioned for the fundamental enlightenment of all existence. In this relation Buddha makes the following suggestions :

All the pluralistic laws which are preached in several instances, do not contradict nor contravene Suchness by their signification. Even the moral books in the world or political words or industry or the like may be explained to the people, they shall all comply with the right law (Yamakawa, pp. 539-40; there are no equivalent lines in Kern).

Hereupon Nichiren emancipated the ordinal conception of religion into the broadest sense, which is the synthetic creation. The moral books in the above quotation, imply philosophy, ethics, literature or the like; political words mean legislation, the judicature and administration, and industry means agriculture, commerce and the manufacturing industry, etc. Nichiren gave this instruction to his disciples:

The priests among my disciples shall be the Masters to the Emperors or the ex-Emperors, and the laymen shall take seats in the Ministry; and thus in the future, all the nations in the world shall adore this law (Works, p. 583)

He goes on to say: “In brief, my religion is the law of the political path” (Works, p. 391).

Therefore, for Nichiren, the professional practice of religion is not only the method, but verily also the justification and purification of our daily lives at every turn. Keeping this in mind, read the following instruction of Nichiren to Shijo Kingo: “Consider your daily works in your Lord's service as being the practice of the Hokekyo” ( Works, p. 893).

Thus, he established the religious method of the synthetic creation, and he decided that the country should be the unit of the worldly salvation. Summing up the salient points, according to Nichiren, if religion really wants to redeem the world, it must religionize the country. Religion as it is cannot religionize the country; it is not worthy of the future religion. He thought that the state is the unit of the world, and that the individual could never be the unit of the world. In other words, it is useless to uphold the fallacy that if religion instructs individuals one by one, the world, will, naturally, sooner or later, become religionized.

On the contrary, let us suppose that the state has the conviction of true morality, and of politics, education and diplomacy, or that everything has been done morally; then the individual who belongs to the state is, as it were, a snake in a narrow and straight bamboo-tube. It may seem like bondage, nevertheless such a right bondage must be welcomed.

Is the so-called free will surely free? Man cannot live without being to a certain extent in bondage, though one may be proud to live and decide everything by one's own free will, for free will, too, is a sort of bondage. Year after year, as readers know, theories and books on ethics are ever increasing, year by year, the numberless doctrines and scriptures of religion are appearing, from year to year, churches, temples and schools are multiplying, but inversely the world and mankind are deteriorating, and criminal statistics are increasing in number as years roll on. Are these not notable phenomena?

Hence the country that is moral must take up as her mission the task of the guardianship and espousal of truth, morality and righteousness with all her accumulated power. However religionized a man may be, if the country is not made just, then even the man of righteousness is liable to be obliged to commit a crime in an emergency for the sake of a nation's covetous disposition. The existing countries of the world are committing monstrous self-contradictions of morality. There is no reason at all for a country to be allowed to do wrong under the pretence of so-called “For the sake of the country,” while the country prohibits all lawlessness and iniquity of the individuals therein. So, to start with, such a fallacy must be eliminated.

Nichiren, therefore, examined the essence of the various countries and he decided upon Japan as being the typical moral country. According to Nichiren, Japan is distinctly the typical country based on strict morality, consequently the mission of Japan consists in setting an example of the moral country to the world (see infra, Chapter V). Therefore, he says: “The first and great Supreme Being shall be established in this country” (Works, p. 104).

Of course, he does not proclaim the monistic theory of the country, but he found an ideal country which is a standard for the pluralistic countries of the world. Nichiren believed the fated destination between the Hokekyo and Japan and between Japan and Nichiren himself as Honge Jogyo. He says:

The Great Master Myoraku says (in his Commentary): The children benefit the world by propagating the law of the Father: Children means here the Saints-out-of-the-earth; Father means the Buddha Shakamuni; World signifies Japan; Benefit the Attainment of Buddhahood; Law the adoration of the Myohorengekyo. It is now the same as ever it was, Father is Nichiren; Children are my, Nichiren's, disciples and adherents; World is Japan; Benefit means accepting and keeping this law and thereby accomplishing the Attainment of Buddhahood; and Law is the Sacred Title bequeathed to us by Honge Jogyo (“Ongikuden”).

But we must be conscious that the “World is Japan.” This is not to be taken literally in this translation nor in the original.

Anesaki gives the following explanation: “In this latter sense, Japan meant for him the whole world” (Anesaki, “Nichiren, the Buddhist Prophet.” Harvard University Press, p. 98).

But this appears to be incorrect because the character of “the World” does not mean here the world in the usual sense, but it means “the World Benefit,” namely one of the Four Siddhanta, the Four Instructive Methods (Shi-shits-dan). In other words, this is a special technical term, the full name is “The Completion of the world with the benefit of delight (Sekai Shits-dan Kangi no Yaku). Hence, “the World is Japan” means “Japan has the mission to propagate the law of the Hokekyo and thereby redeem the world.”

As we have seen above, Nichiren beheld the signification of the relation between the Hokekyo and Nichiren himself through the fact of the wonderful combination of Japan. According to him the world must be united as brethren, namely as a moral world, and in the future the Holy Altar of the Hokekyo, especially of the Honmon centric commandment, shall be established in Japan. He says in one of his significant essays, “On the Three Great Secret Laws” (San dai Hiho Sho):

At a certain future time, when the state law will unite with the Buddhist law and the Buddhist law harmonizes with the state law, and both sovereign and subjects will keep sincerely the Three Secret Laws, then will be realized such a golden age in the degeneration of the Latter Law, as it was in olden times under the rule of King Utoku. Thus the Holy Altar will be established with Imperial Sanction or the like at a place like the excellent paradise of Vulture Peak. We must only prepare and await the advent of the time. There is no other law or commandment which is practicable, only this one. This Holy Altar is not only the sanctuary for all nations of three countries (India, China and Japan) and the whole world, but even the great deities, Brahma and Indra, have to descend in order to initiate into the perfect truth of the Hokekyo (Works, pp. 240-41).

Once Ibsen proclaimed “The Third Empire.” Nichiren had systematized and proclaimed it nearly seven hundred years ago. Thus, he established the Three Great Secret Laws and left them to deal with the future world. Nichiren's religion is, in fact, the principle of synthetic creation. Therefore in Nichirenism everything can be brought into harmonization. It is evident that he proclaims the necessity of subjecting all countries to one moral law, approving, of course, the pluralistic existence of all countries. But it is totally different from the Utopian's fancy, because of his positive adoption of all material forces.

Therefore the commandment of his religion is recognized by the act of keeping and practising the Hokekyo for his own sake and at the same time for the sake of human kind. Consequently, the vow and its practice are the essential elements in his religion. In order to keep the law bodily means that in daily life we must be determined to do anything. Rich men shall protect the law by means of their wealth and learned men shall extend the law by means of their knowledge and wisdom, etc. All the accumulated power of human civilization must make it a duty to help to realize the law on the earth. In an emergency, we shall be martyrs to the law. In short, we must keep the law for dear life and then the sincerity and signification of life will be realized.

Such being the case with individuals, the country, too, must be established on righteousness. The country is, indeed, an organ for the realization of the moral law of security with all her accumulated powers. When the country attains to such conviction that it becomes the highest organ for the protection of righteousness, and that it can sacrifice itself whenever it is obliged to do so for the sake of the law, then the ideal world will be realized before our very eyes. The Holy Altar is mentioned for this purpose.

To realize this ideal we are expected to have absolute faith even at the risk of our lives. Although persecution, innumerable difficulties and troubles might be our lot we could go through fire and water if our faith were strong and true. Nichiren exclaims with firm conviction:

It appears to be the age when the five characters of Myohorengekyo, which is the essence of the Scripture, which is the principal object in view of all the Buddhas, shall be propagated over the world, which is the beginning of the Latter Law. At this time, I, Nichiren, have taken upon myself the task of pioneering, although even those great men, Kasho and Anan, etc., Memyo and Ryuju, etc., and Nangaku, Tendai, Myoraku and Dengyo had not propagated this law for over 2220 years since Buddha's Death: My young men and women, ye shall come in quick succession, and excel, in the propagation of this law, those sages Kasho and Anan and likewise those great men Tendai and Dengyo. If you stand in fear of threats by the King or the like (the Hojos and the official authorities) of so small an island, how would you fare if you confronted Enma's Throne of Judgment (Works, p. 393).

Nichirenism, as already stated, taught us the most sincere vow for dear life in order to render life significant and truly happy, and now the modern Nichirenism teaches us how to realize such an ideal in the world. Thus a Nichirenian's idealism is not a mere spiritualism, but a concrete motion with material forces, it is possible therefore for direct action to follow in an emergency.

Imaginative gods, fanciful views of reality, superstitions, and egoistic faith are, all of them, denied in Nichirenism. These Three Great Secret Laws are the Key to the future civilization. Recent civilization has brought about the freedom of the masses and equality by depriving the nobility of their freedom. Although people may call their own action righteousness, it is, indeed, merely freedom and equality of the commons just as it was arbitrariness in the case of the nobility. In Nichiren's thought such one-sided righteousness is denied absolutely.

Nichiren expected to establish his ideal country, heaven on earth, by the incessant efforts of all his followers in the future. But the world will fall into evil ways, nay into folly with its struggles; for instance, capitalism against labour, socialism against aristocratism, individualism against nationalism, diabolism against humanism, etc., while religion or ethics is constantly somniloquising. Finally, the world might fall into extreme confusion just like modern Russia. Should it happen thus, all human beings and all countries would awaken and heed Nichiren's warning, so thought Nichiren. He speaks the following words:

At a future time, a war more stupendous than any before will be waged, when it comes all beings under the light of the Sun and Moon will pray for mercy to all manner of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas out of fear of the ruin of their countries or lives: If in spite of that they do not receive divine favour, then, for the first time, innumerable priests and all the great kings will believe the hated priestling (i.e. Nichiren himself), and all people will call upon the Sacred Title, making the sincerest vows and joining hands, just as when the Buddha performed the Ten Mysterious Powers (miracles) in Chapter XXI of the Hokekyo, and all existence without exception in the ten directions, shouted ‘Adoration to the Buddha Shakamuni, Adoration to the Buddha Shakamuni and Adoration to the Perfect Truth of the Hokekyo, Adoration to the Perfect Truth of the Hokekyo’ towards this world loudly in the same breath (Works, p. 111; and see Tanaka: “Nichiren's Doctrine”).

Nichiren's religion was founded with such a future aim, and was not well understood at that time nor even at the present day. But the time is drawing nigh when this religion will be accepted. The Great War, in a sense, may be an omen that Nichiren mentioned when he said the greatest war on record. To the problem between the country and religion, or that of ethics and religion, the Key of possible solution is given here, I think.

Now let us learn about the life Nichiren led and how he came upon these remarkable thoughts and the reason for his special admiration of Japan.

To be continued…