THEORY OF THE END - Part 7: The "Desacralization" Problem (or "The Death of the Sacred")

The seventh part of a series exploring various theories on the end of human civilization.

[Note, this is just one entry in a long ongoing essay series. If you enjoy this entry, please consider visiting my page and reading the others.]

IV. The “Desacralization” problem

In early 2025, the Pew Research Center conducted what they called “The Religious Landscape Study (RLS)” using a survey of 36,908 American adults. In a February article, they highlighted the results as follows:

The first RLS, fielded in 2007, found that 78% of U.S. adults identified as Christians of one sort or another. That number ticked steadily downward in our smaller surveys each year and was pegged at 71% in the second RLS, conducted in 2014.

The latest RLS, fielded over seven months in 2023-24, finds that 62% of U.S. adults identify as Christians. That is a decline of 9 percentage points since 2014 and a 16-point drop since 2007.

While they noted that the decline in religiosity among US adults had either slowed or leveled-off, the levels we have seen in recent years are the lowest in recorded history. This should not be a surprise to anyone who has been paying attention to such matters, and it was a phenomenon that Francis Fukuyama noted several decades ago, at the end of the 80s. One of the major driving forces behind it, in his view, was freedom of belief and the sheer amount of options available to the average person:

[People] are faced with an almost insuperable problem. They have more freedom to choose their beliefs than in perhaps any other society in history: they can become Muslims, Buddhists, theosophists, Hare Krishnas, or followers of Lyndon LaRouche, not to speak of more traditional choices like becoming Catholics or Baptists. But the very variety of choice is bewildering, and those who decide on one path or another do so with an awareness of the myriad other paths not taken.

More than just fancy metaphysical theory, however, religion seeks the pearl of supreme truth in regards to the greater universe and our place within, and it strives to apply this truth to the way we live our lives. “... We must rid ourselves of any conception which looks upon religion as a function for the fulfilment of men's arbitrary will,” Kishio Satomi writes in his book “Japanese Civilization: Its Significance and Realization.” “Religious faith which is not supported by truth… always results in failure.”

But if this is the case, which religion actually holds the highest truth? Is it possible to explore each and every religion in enough depth to assess such a thing? This is but one factor that has contributed to the large-scale “desacralization” of modern society. One may ask why I use that term instead of “secularization.” The reason is that they are two separate concepts. “Secularization” implies the separation of social norms and governing institutions from the domain of religion, which has already been accomplished for some time.

The “secularized” view of religion as a mere personal endeavor meant to pacify the soul is now the default view. This is not a new or controversial observation. In fact, Professor Satomi heavily criticized this faulty conception of religion in his book “Discovery of Japanese Idealism,” which was published all the way back in 1924:

Most people, first of all, satisfy their appetite, then their carnal desire, then material desire, and, having satisfied these yearnings some of them who belong to a rather superior class listen to the preachings of the way of God to stimulate the desire of sleep. They substitute preachings and religious music for lullabies.

He writes again in “Japanese Civilization”:

Thus, actual life is religion and religion is actual. The depravity of all religions from olden times to the present day has its root in the fallacy of a vague dualism of actual life and religion. Therefore religion is justified in leading and criticizing life in all its aspects. Religion must be woven into actual life, otherwise it would appear to be of no avail.

But think about it: would such a view of religion even be possible in today’s environment? Francis Fukuyama apparently does not believe so, as it would violate the foundational principles of Democratic Liberalism, which he believes to be a sort of terminus in the evolution of civilizational organization. He writes in “The End of History and The Last Man”:

Like nationalism, there is no inherent conflict between religion and liberal democracy, except at the point where religion ceases to be tolerant or egalitarian… Christianity in a certain sense had to abolish itself through a secularization of its goals before liberalism could emerge. The generally accepted agent for this secularization in the West was Protestantism. By making religion a private matter between the Christian and his God, Protestantism eliminated the need for a separate class of priests, and religious intervention into politics more generally. Other religions around the world have lent themselves to a similar process of secularization: Buddhism and Shinto, for example, have confined themselves to a domain of private worship centering around the family.

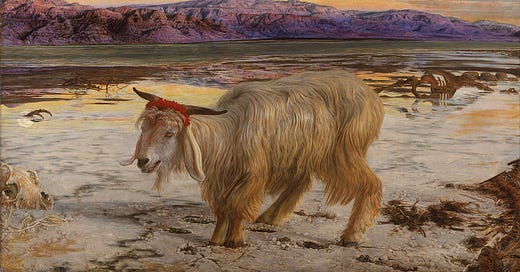

What Fukuyama fails to note here is that this amounts not only to secularization, but also “desacralization.” For the purposes of this essay series, my use of the latter term indicates not just irreligiosity, but the total inability for the citizen to be fully religious. When public life is removed entirely from the realm of the sacred and religion becomes a mere matter of inner thought rather than a conception of supreme truth through which one governs both themselves and others, it castrates religion (all religion) and renders it harmless before turning instead towards something else; abandoning conventional gods for strange new ones.

One can be as dedicated to their religion as possible in private, but this faith will inevitably be overruled by a secular and morally bankrupt state, which is (supposedly) the representation of the collective will of a people. Kishio Satomi knew this well, writing in the third chapter of “Japanese Civilization”:

The country or the state, of course, is the secondary production of human life because of the order of its origination, but as a matter of fact, with regard to our present civilized world, individual beings are preceded by the country. With regard to the method of salvation, the country must be classed as the unit…

… the country that is moral must take up as her mission the task of the guardianship and espousal of truth, morality and righteousness with all her accumulated power. However religionized a man may be, if the country is not made just, then even the man of righteousness is liable to be obliged to commit a crime in an emergency for the sake of a nation's covetous disposition.

This is the reason why the Edo-era Zen Master Suzuki Shosan was so intent on petitioning the Shogunate to recognize Buddhism as “the truth,” as at the time it was more preoccupied with the far more secular philosophy of Japanese Neo-Confucianism. If the country could recognize his faith as true, then it follows that the people eventually would as well. He is recorded in his book of sayings (“Roankyo”) as stating the following:

I want to propose my way of government, the upholding of Buddhism, formally to the authorities. Heaven hasn't let me do it yet, though. For one thing, the Buddhism which the patriarchs and predecessors have left us at the cost of bloody tears and relentless practice, has fallen to ruin because there's no official decree to support it. Our greatest problem is the way Buddhism's been dropped and gets no outside protection. Because I'm sure Buddhism will never be recognized as the truth unless the government so ordains. My deep desire is to present this proposal as boldly as I can. I'll say, 'I await most steadfastly and humbly your edict, that Buddhism shall be recognized as the truth.’

However, this kind of declaration would be impossible in our technically-inclined and supposedly Liberal Democratic system because it would run counter to its foundational values. In effect, what we are now witnessing is the death of the sacred, caused not only by the removal of the sacred from the view of the public’s collective consciousness and the aforementioned plurality of religious frameworks available to us, but the total demystification wrought by the material preoccupation of modernity; a topic we will explore in more depth in later chapters (this is just a preliminary exposition of this particular set or circumstances).

Fukuyama, adopting Hegel’s understanding of religion, does not see this as a detriment. Instead it is merely a necessary casualty of the unfolding weltgeist. Religion, in his view, was important for its social utility, but does not represent a true expression of the ultimate. It is a tool to be discarded once its usefulness has played itself out. As he writes in “The End of History”:

The world's great religions, according to Hegel, were not true in themselves, but were ideologies which arose out of the particular historical needs of the people who believed in them. Christianity, in particular, was an ideology that grew out of slavery, and whose proclamation of universal equality served the interests of slaves in their own liberation…

According to Hegel, the Christian did not realize that God did not create man, but rather that man had created God. He created God as a kind of projection of the idea of freedom, for in the Christian God we see a being who is the perfect master of himself and of nature. But the Christian then proceeded to enslave himself to this God that he himself created. He reconciled himself to a life of slavery on earth in the belief that he would be redeemed later by God, when in fact he could be his own redeemer.

Yet this presents a problem which Fukuyama finds unable to ignore: that being the issue of motivation. It’s no secret that man is willing to build breathtaking monuments and cathedrals in service of a higher power, but it does not appear that he is willing to do the same for the sake of Liberal Democracy.

If Auguste Comte, often considered the father of Sociology, could not rouse the spiritual vigor of man through his non-theistic “Religion of Humanity,” then it should come as no surprise that a system composed primarily of bureaucratic drudgery would fail even more spectacularly. There is no man who would willingly sacrifice his life for the Bureau of Motor Vehicles. G. K. Chesterton writes on this matter in his book “Heretics”:

In an age of dusty modernity, when beauty was thought of as something barbaric and ugliness as something sensible, [Comte] alone saw that men must always have the sacredness of mummery. He saw that while the brutes have all the useful things, the things that are truly human are the useless ones. He saw the falsehood of that almost universal notion of to-day, the notion that rites and forms are something artificial, additional, and corrupt. Ritual is really much older than thought; it is much simpler and much wilder than thought.

A feeling touching the nature of things does not only make men feel that there are certain proper things to say; it makes them feel that there are certain proper things to do. The more agreeable of these consist of dancing, building temples, and shouting very loud; the less agreeable, of wearing green carnations and burning other philosophers alive. But everywhere the religious dance came before the religious hymn, and man was a ritualist before he could speak. If Comtism had spread the world would have been converted, not by the Comtist philosophy, but by the Comtist calendar.

By discouraging what they conceive to be the weakness of their master, the English Positivists have broken the strength of their religion. A man who has faith must be prepared not only to be a martyr, but to be a fool. It is absurd to say that a man is ready to toil and die for his convictions when he is not even ready to wear a wreath round his head for them. I myself, to take a corpus vile, am very certain that I would not read the works of Comte through for any consideration whatever. But I can easily imagine myself with the greatest enthusiasm lighting a bonfire on Darwin Day.

Regardless, modern civilization’s pervasive desacralization means that Liberal Democracy has been operating on what one could label “legacy social infrastructure” inherited from the religions of prior eras, infrastructure that is now wearing out and breaking down. This potential pitfall did not escape Fukuyama’s notice. He bemoans:

Capitalist prosperity is best promoted by a strong work ethic, which in turn depends on the ghosts of dead religious beliefs, if not those beliefs themselves, or else an irrational commitment to nation or race. Group rather than universal recognition can be a better support for both economic activity and community life, and even if it is ultimately irrational, that irrationality can take a very long time before it undermines the societies that practice it.

I would append to this the issue of societal order, which also deteriorates as religious influence is increasingly dissolved. When religious ideals are instilled in the greater public, there exists a propensity for self-governance that does not exist in a materialistic and atheistic culture. Even if this propensity is only marginal, it can make a significant difference in the aggregate, and without it order can only be established through more heavy-handed means.

But there is yet another facet of Liberal Democracy’s unraveling that has been dramatically exacerbated by the secularization and desacralization outlined above, that being the “atomization” problem, which we will cover in the next chapter.

Until then, thank you all very much for reading.

To be continued…

Fukuyama hit the nail in the head. It's interesting because I had come to similar conclusions just based on observation. To use one example, the Roman Catholic Church between the modernist/anti modernist conflicts and the full victory of secularized neutered Catholicism after Vatican II.

It's reflected even in the language the popes use, in that Christ as been replaced by climate change or the brotherhood of man. The entire supernatural reason for the Church has been turned on its head to focus on secular, this world issues.

I always saw that IF a certain religion was true than it demands to color every aspect of life, both public and private. This is anathema in the modern world which demands religion be a strictly private affair.

Islam in certain areas is one of the only mainstream religions left whose adherents ( at least in part) still believe that if Islam is true than ALL of life should be governed by it. I don't think this will last either, as bowing to secularism and modernity tend to rot out the fundamentals of every religion.

But what is the answer? I wish I knew. I think part of the issue is there really isn't any way to know which of these religions are "true" or if all of them are man made fables to keep people in line. It's impossible to know.

When everybody in your life was Christian or Muslim and the society reflected that it was probably easier to believe your holy book and tradition.

In the modern world everybody has equal access to all the world's great spiritual wisdom, none of the religious leaders actually believe a lick of it anymore, and modern secularism has no place for religion that doesn't become a purely private affair.