THEORY OF THE END - Part 18: The Quality of Time (and its Dissolution)

The eighteenth part of a series exploring various theories on the end of human civilization.

“It's always out there, just past the 7-11, around the cloverleaf… the darkness that waits for me. Can't see it unless I turn away. It's not there when I don't look. Waits for me to come back. Waits for me to come sink in. Just waiting…”

-Information Society, from “Closing In”

The end of the 19th century saw theoretical physics entering into a moment of crisis around the properties of light. One of the men responsible was James Clerk Maxwell, who believed, along with other scientific thinkers of the 19th century, that light waves were propagated through some kind of material ether. However, as Thomas Samuel Kuhn writes in his book on “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” Maxwell’s own electromagnetic theory of light “gave no account at all of a medium able to support light waves, and it clearly made such an account harder to provide than it had seemed before.”

Maxwell's theory was initially met with skepticism for this reason, but as it proved proficient in its predictive abilities, it “achieved the status of a paradigm” and “the community’s attitude toward it changed.” Yet the problem of the ethereal component still remained a thorn in the side of theoreticians. Kuhn continues:

The years after 1890 therefore witnessed a long series of attempts, both experimental and theoretical, to detect motion with respect to the ether and to work ether drag into Maxwell’s theory. The former were uniformly unsuccessful…

The puzzle remained unsolved until the introduction of Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity in 1905, which dramatically changed the way physicists saw both space and time (now collectively called “spacetime”), recontextualizing them as "relative,” i.e. they would act differently depending on the mass, positioning, and velocity of the bodies in question. Bodies “warp” or “curve” spacetime, causing gravity (and therefore movement) as well as a shift in the way light is observed and time is experienced.

The last of the above effects is perhaps the most difficult to wrap one’s head around, as it implies that time itself changes depending on a body’s speed or the strength of gravitational force acting upon it slowing down with the increase of either. As one would expect, scientists eventually put this theory to the test when they had devised the means to do so, with one such effort now called the “Hafele-Keating experiment.”

In 1971, Joseph Hafele and Richard Keating, intent on exploring this supposed “clock paradox,” placed four atomic clocks onto regularly scheduled commercial airplane flights. The general concept behind the experiment was simple: first they would fly the clocks around the world in the Eastern direction, the direction of the Earth’s rotation, and measure the change in time against the stationary clocks at the United States Naval Observatory. Next, they would repeat the process, but instead fly the clocks Westward, against the Earth’s rotation. A 1971 Time Magazine article on the experiment, entitled “A Question of Time,” recounts the theory behind it as follows:

The paradox, which stems from Einstein's 1905 Special Theory of Relativity, is difficult for the layman to comprehend and even harder for scientists to prove. It means that time itself is different for a speeding automobile, for example, than for one parked at the curb. The natural vibrations of the atoms in the engine of the moving auto, the movement of the clock on the dashboard and even the aging of the passengers occur more slowly than they do in the parked car. These changes are imperceptible at low terrestrial speeds, however, and according to the theory become significant only when the velocity of the moving object approaches the speed of light.

According to the paper study eventually published in the journal “Science,” the results of the airplane experiment were “in good agreement with predictions of conventional relativity theory.” It continues:

Relative to the atomic time scale of the U.S. Naval Observatory, the flying clocks lost 59±10 nanoseconds during the eastward trip and gained 273±7 nanoseconds during the westward trip, where the errors are the corresponding standard deviations. These results provide an unambiguous empirical resolution of the famous clock "paradox" with macroscopic clocks.

Indeed, it appears that, just as Einstein had predicted, time was relative depending on the conditions, or one could say “quality,” of the fabric of spacetime. Considering this startling discovery, what else could there be to learn about time? Could there perhaps be other “qualities” which we are overlooking due to a collective lack of perceptive ability? The French metaphysician Rene Guenon would say “yes.”

If we accept the circular model of time, as discussed in previous chapters, as well as the notion that time is relative, then the logical conclusion is that time itself could potentially change in quality depending on one’s position in a cosmic macrocycle. “According to the different phases of the cycle,” Guenon writes, “sequences of events comparable one to another do not occupy quantitatively equal durations.” This essentially means that the last phases of a cosmic cycle would unfold with higher rapidity. Guenon elaborates using Hindu doctrine as his example of choice:

… this is particularly evident in the case of the great cycles, applicable both to the cosmic and to the human orders, the most notable example being furnished by the decreasing lengths of the respective durations of the four Yugas that together make up a Manvantara. For that very reason, events are being unfolded nowadays with a speed unexampled in the earlier ages, and this speed goes on increasing and will continue to increase up to the end of the cycle…

The above-mentioned decrease in lengths for subsequent cycles is described in a footnote as “known to be proportionate to the numbers 4, 3, 2, 1,” meaning that the first part of the “yuga cycle” is four times longer than the last (the “Kali Yuga,” in which we are said to currently reside). This is not an instant shift, of course, rather it is an effect that Guenon believes to unfold gradually, like “the movement of a mobile body running down a slope and going faster as it approaches the bottom.”

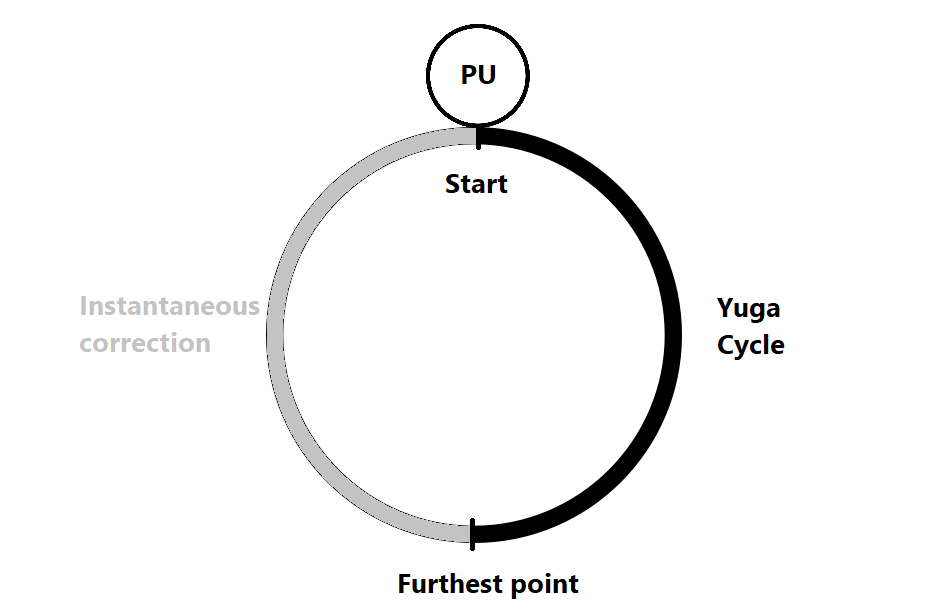

In this illustration, what the “mobile body” is theoretically retreating from at the top of the hill is termed the “principal unity” by Guenon, and can be conceived of as the ultimate source which all traditional spiritual pursuits strive to realize, thus the cycle is characterized as a downward movement away from a supreme primordial unity. This movement terminates at the furthest point, when time has been condensed into a single moment, and the process rectifies itself instantaneously; a sudden “inversion of the poles,” like an hourglass being flipped over.

We can craft another illustration of Geunonian cyclical time using the Theory of Relativity as a guide by picturing a circle with the “principal unity” (PU) occupying the top end. The four divisions of the yuga cycle would be represented by the first half of the circle, while the instantaneous correction is represented by the second half. Thus the end of the cycle would actually occur at the point furthest from the principal unity, time speeding up as the cosmic location drifts away from what can be viewed as the spiritual gravitational pull of the principal unity.

It must be clarified, however, that this is not an objective description of how this metaphysical process works, but rather a visual model for understanding the principles that Guenon laid out in his text. The truth is that we cannot fully comprehend exactly how it works due to modern man’s severed connection to the higher realms. In fact, the effects of this quantum shift have gone largely unnoticed by us. That does not mean, of course, that we do not experience them.

One potential ramification of the phenomenon that Guenon cites is the faster passing of life: “human life itself is moreover well known to be considered as growing shorter from one age to another,” he writes, “which amounts to saying that life passes by with ever-increasing rapidity from the beginning to the end of a cycle.” In this sense, it is not that we are living for fewer years, but that the years themselves are exhausting themselves faster. This is also reflected in noticeable behaviors that are usually blamed on more material or sociological factors. Guenon states:

It is sometimes said, doubtless without any understanding of the real reason, that today men live faster than in the past, and this is literally true; the haste with which the moderns characteristically approach everything they do being ultimately only a consequence of the confused impressions they experience.

This is far from the only observable social phenomenon, however, with the most notable being what Guenon calls “the reign of quantity.” It can be described as an almost obsessive preoccupation with boiling all things down to their “quantity” to the detriment of their “quality,” not only in the realm of material goods (standardization and lowering of artisanal quality), but in the way we view the world around us. This is very pronounced in the realm of science (and, by extension, “Scientism”), which is by nature quantitative due to the ever-present necessity of scientific measurement, but is, of course, not limited to that field, as Guenon explains:

This tendency is most marked in the ‘scientific’ conceptions of recent centuries; but it is almost as conspicuous in other domains, notably in that of social organization — so much so that, with one reservation the nature and necessity of which will appear hereafter, our period could almost be defined as being essentially and primarily the ‘reign of quantity’. This characteristic is chosen in preference to any other, not solely nor even principally because it is one of the most evident and least contestable, but above all because of its truly fundamental nature, for reduction to the quantitative is strictly in conformity with the conditions of the cyclic phase at which humanity has now arrived…

What I found particularly interesting about this description is how much it overlaps with what Jacques Ellul had written about in his book “The Technological Society.” The similarity is effectively summarized in a brief passage which reads: “it might be said that technique is the translation into action of man’s concern to master things by means of reason, to account for what is subconscious, make quantitative what is qualitative, make clear and precise the outlines of nature, take hold of chaos and put order into it.”

An example of this principle in action is public opinion analysis, regarding which Ellul states:

This system brings into the statistical realm measures of things hitherto unmeasurable. It effects a separation of what is measurable from what is not. Whatever cannot be expressed numerically is to be eliminated from the ensemble, either because it eludes numeration or because it is quantitatively negligible. We have, therefore, a procedure for the elimination of aberrant opinions which is essential to the understanding of the development of this technique. The elimination does not originate in the technique itself. But the investigators who utilize its results are led to it of necessity. No activity can embrace the whole complexity of reality except as a given method permits. For this reason, this elimination procedure is found whenever the results of opinion probings are employed in political economy.

This is, in my opinion, a fantastic illustration, as it shows quite clearly the limitations of the type of quantitative analysis which our modern civilization gravitates towards, and this same tendency towards uniformity can be observed in countless areas, from psychology, to statistics, to sociology, to economics, to political theory. As we witness the flourishing of the global economy and its deterritorializing and reterritorializing effects (which manifest as the sweeping artificial commodified replacement of all prior paths towards meaning and identity), we can see a tendency towards uniformity overtake our very minds as well.

“Technique, to be used, does not require a ‘civilized’ man,” Ellul states. “Technique, whatever hand uses it, produces its effect more or less totally in proportion to the individual’s more or less total absorption in it.” What this means is that the reign of efficiency, and therefore the domination of quality by quantity, can only result in the eventual “technicization” or “mechanization” of mankind itself. And this is exactly what is happening, as Rene Guenon writes:

The conclusion that emerges clearly from all this is that uniformity, in order that it may be possible, presupposes beings deprived of all qualities and reduced to nothing more than simple numerical ‘units’; also that no such uniformity is ever in fact realizable, while the result of all the efforts made to realize it, notably in the human domain, can only be to rob beings more or less completely of their proper qualities, thus turning them into something as nearly as possible like mere machines; and machines, the typical product of the modern world, are the very things that represent, in the highest degree attained up till now, the predominance of quantity over quality.

There is a sort of irony in all of this, specifically the idea that, as man retreats from what Guenon calls “the principle unity,” that great spiritual center from which all existence emanates, he “unifies” himself in a very mechanical, artificial way. It is almost a mockery of the kind of unity that more spiritual men of the past desperately sought, one which occupies a decidedly lower stratum of existence. Guenon calls this seemingly paradoxical, but ultimately logical, phenomenon “uniformity against unity.” He continues:

The consequence, paradoxical only in appearance, is that to the extent that more uniformity is imposed on it, the world is by so much the less ‘unified’ in the real sense of the word. This is really quite natural, since the direction in which it is dragged is, as explained already, that in which ‘separativity’ becomes more and more accentuated; and here the character of ‘parody’, so often met with in everything that is specifically modern, makes its appearance.

It must be emphasized that numbers, despite being “uniform,” are not “unified,” rather they are separate by nature. Modern man, as a component of his complete desacralization, is molded from birth by the numerical in the form of finances, science, psychological evaluation, algorithms, governmental policy, demographic profiling, etc… thus we are stricken with a profound atomization, despite being surrounded by other humans and despite all of the technology which was intended to link us together. Always together, yet forever alone.

This is further exacerbated by philosophies like Rationalism, which is individualistic in that it denies “everything that is of a supra-individual order” and tasks its adherents with formulating a “rational” worldview through their own power (as Gueonon states: “rationalism and individualism are thus so closely linked together that they are usually confused”). It simultaneously promotes a fallacious view of human homogeneity by presuming that the “reason” of all human beings works identically. This creates the misunderstanding held by so-called “rational” thinkers that people from radically different times and places mentally operate in the same manner they do. Guenon elaborates as follows:

Human nature is of course present in its entirety in every individual, but it is manifested there in very diverse ways, according to the inherent qualities belonging to each individual; in each the inherent qualities are united with the specific nature so as to constitute the integrality of their essence; to think otherwise would be to think that human individuals are all alike and scarcely differ among themselves otherwise than solo numero.

The inevitable consequence of the “reign of quantity” discussed in this chapter is the complete shackling of the man to the realm of the material, severing him from the subtle influences of higher states of being. “… never have either the world or man been so shrunken,” writes Guenon, “to the point of their being reduced to mere corporeal entities, deprived, by hypothesis, of the smallest possibility of communication with any other order of reality!”

This in itself is a dreadful thought. Indeed, modern man’s distance from men of the remote past is already extremely wide if we limit ourselves to the current conventional modes of analysis like psychology and materialism, a fact that has led to us so quickly labeling the men of prior ages “naïve,” “childish,” and "superstitious” for their vastly different worldviews. If we accept the idea that our very perceptive abilities have been limited by the constraints of the modern condition, the gulf widens to an absolutely staggering degree.

Thus we arrive at the disturbing and very real possibility that subtle forces we can’t sense or comprehend are influencing us in undetectable ways, whether these forces are benevolent or, more likely, malevolent; of a lower plane of existence than even our material one. “It can be said with truth that certain aspects of reality conceal themselves from anyone who looks upon reality from a profane and materialistic point of view,” Guenon writes. “They become inaccessible to his observation.” He continues:

… this is not a more or less ‘picturesque’ manner of speaking, as some people might be tempted to think, but is the simple and direct statement of a fact, just as it is a fact that animals flee spontaneously and instinctively from the presence of anyone who evinces a hostile attitude toward them. That is why there are some things that can never be grasped by men of learning who are materialists or positivists, and this naturally further confirms their belief in the validity of their conceptions by seeming to afford a sort of negative proof of them, whereas it is really neither more nor less than a direct effect of the conceptions themselves.

Thus modern man makes the fatal mistake of believing that the infernal shadow of malefic subtle influence does not exist as long as he does not observe it. “It's not there when I don't look.” Yet these are the exact conditions necessary for such a force to overtake the material world, plunging it into a darkness that we can’t even begin to comprehend.

However, there is another aspect to this that must be addressed, that being the aforementioned final “correction” proposed by Guenon in his exposition of the cosmic macrocycle. In service of this, Guenon offers monetary policy as a helpful analogy. Stripped of any higher quality which may have limited the abuse of currency, or as Guenon says “the guarantee of a superior order,” what we see is its continual devaluation:

… it has seen its own actual quantitative value, or what is called in the jargon of the economists its ‘purchasing power’, becoming ceaselessly less and less, so that it can be imagined that, when it arrives at a limit that is getting ever nearer, it will have lost every justification for its existence, even all merely ‘practical’ or ‘material’ justification, and that it will disappear of itself, so to speak, from human existence…

… the real goal of the tendency that is dragging men and things toward pure quantity can only be the final dissolution of the present world.

What’s notable about this is that, like most traditional models of cyclical time, it presents a view that is fundamentally the opposite of the progressive narrative that has held Western civilization under its heel for so long. Indeed, such opposition is a key factor in Guenon’s understanding of Traditionalism. As for the aforementioned “dissolution,” however, exactly how it may play itself out will be explored in a later chapter, but I should make it clear here that I do not share the pessimism of Rene Guenon regarding this issue, even if our views do overlap to a certain extent.

In fact, as a Buddhist, I am basically obligated to diverge from his belief in a closely looming end stage of humanity, as the Buddhist understanding of time and cycles (although it indeed shares some features with the Guenonian model) differs to a significant degree. In the next couple of essays, I will outline the relevant differences for you using both a historical and eschatological analysis of Buddhist scripture.

Until then, thank you all very much for reading.

To be continued…